Alibaba Valuation and China Deep Dive

Alibaba is as beaten down as ever. Is this a huge opportunity or is China simply uninvestable? Let's take a look!

Content:

An Introduction to Investing in China

China’s Economic State

Introduction

The Main Problems

The Big Picture

The Debt Trap

Consumer Sentiment, A Slow Economy, and Deflation

The Taiwan Conflict

Summary of the Macroeconomic Risks

Alibaba’s Business Model

Introduction to the Business Segments

Alibaba’s Financials

Cloud Deep Dive

Global Cloud Market

Chinese Cloud Market

AliCloud

Taobao and TMall Deep Dive

Chinese E-Commerce

Expanding Globally

Personal Fit and Risks

Risk Tolerance

Sizing

My reasons for being invested

Catalysts

Microeconomics

Macroeconomics

Valuation

Discounted Cash Flow Analysis

Reverse Discounted Cash Flow Analysis

Extra Note

First of all, if you see value in these deep dives, I publish one every month. Subscribe to never miss one again:

An Introduction to Investing in China

As a value investor, I’m usually looking for bets that offer unlimited upside and limited downside. That’s the best-case scenario. In reality, while you can find asymmetric bets, few of them will actually have a limited downside and simultaneously offer a huge upside. If you want to find such investments, you need to look in places that are less efficient than internationally well-known large caps. (We’ll do that, by the way, in the next Deep Dive that will focus on an Italian mid-cap).

Alibaba is no such business. The possible upside is huge, but there are many questions regarding its downside potential. As we will see, the financial strength of Alibaba’s business offers a significant margin of safety microeconomic-wise. However, the macroeconomic side of investing in China comes with many risk factors and unknowables. You invest in a country where one person has the power to do whatever he wants and an ideology that companies should not earn huge excess cash. However, that didn’t seem to bother anyone for years, in and outside of China.

After researching China more in-depth, my guess is that China’s leadership wants to see their international companies, especially the technological innovators, succeed rather than cripple them with regulation. Every now and then, they will need to set an example to show they are still the monopoly of power which will result in some headlines and perhaps some little fines. This can, once again, scare investors and compress multiples. The underlying businesses, however, barely change.

But that’s just an introductory hypothesis, let’s start with analyzing the facts.

China’s Economic State

There are three main problems we currently read about in the media.

China’s Debt Trap

Weak Consumer Sentiment, A Slow Economy, and Deflation

The Taiwan Conflict

Before we discuss each, let’s take a broader view.

The Big Picture

With more than 1.4 billion people, China is the most populated country on earth, has the fastest-growing middle class in the world, and remains one of the fastest-growing economies in the world.

According to McKinsey’s China Consumer Report 2023: “There is still no other country that adds as many households to the middle class each year as China does. And increasingly, these households are joining the ranks of the upper-middle and high-income bracket, with annual incomes above RMB160,000 (~$22,000). Over the next three years, China is expected to add another 71 million upper-middle and high-income households.”

Another crucial part of the bull case for China is the global dependency on China’s economy. If China struggles, so does the world. That’s why the economic interests of China are more aligned with economies worldwide than recent news make it seem at first glance (or, better said, the other way around). Take a look at this visualization of China’s trade balance:

China is also directly or indirectly responsible for millions of jobs worldwide. Mineral-exporting countries such as Brazil and Australia would suffer from weaker demand in China, and some of the biggest economies in Europe rely on China for rare earth materials. Ursula Von Der Leyen, the EU Commission President, said: “This is an area where we rely on one single supplier – China – for 98% of our rare earth supply, 93% of our magnesium and 97% of our lithium – just to name a few.”

These materials are essential for the production of phones, electric vehicles, solar panels, or semiconductors. In short, there is no way a modern society and economy will run without them.

Because of this, the EU made plans for a de-risking strategy that focuses on diversifying trade partners, looking for alternative sources for rare earths, and producing its own semiconductors. The goal is to produce 20% of the global market’s need for semiconductors in Europe in 2030. Germany wants to take the lead here, and Intel, as well as TSMC, will build factories in Germany with an investment at the size of about 15 billion Euros.

This is a first step, however, this policy is controversial in many ways, and it’s also unknown how the rare earth problem should be solved, considering that demand will only grow in the future. According to the World Bank, demand is expected to increase by 500% by 2050 due to the acceleration of the green transition.

While diversifying trade partners can resolve some of the dependency, Europe is simply lacking its own rare earth resources, which will sooner or later result in even more trade with China.

China is also becoming a leading exporter of some of the most important goods and services for future economies. The times when China produced cheap and low-quality goods are over. China is now the world’s biggest car exporter and accounts for over 50% of global EV (electric vehicle) sales and 70-90% of every stage in battery and solar production.

There is no sustainable future without China. Not only because of their importance in green technologies but also because of their huge impact on global warming. Without China, the goal to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels is impossible to achieve.

The good news is that China, and Xi Jinping especially, are aware of the importance of climate change, and while they are still one of the largest emitters of emissions, they are also leaders in the expansion of renewable energies.

Now that we have a perspective on the big picture, let’s discuss the four problems China currently faces and see how big they really are and what they will mean for the Chinese economy and, therefore, Chinese companies like Alibaba.

1. The Debt Trap

Over the last two decades, China’s growth depended heavily on infrastructure and property investments financed by debt. Real estate now accounts for over 30% of the national GDP and over 80% of household wealth. China’s property developers collectively owe more than $390 billion to various suppliers.

How did this bubble build up?

Historically, the Chinese population preferred real estate over investments in pensions or stocks. There’s also a cultural component to this. Owning real estate in the form of an apartment is a common prerequisite for marriage. Thus, real estate investments seemed to be a no-brainer, for developers and Chinese citizens.

The growth was additionally fueled by government stimulus following the financial crisis of 2008. State-owned steel and cement firms were sitting on massive inventory, which led to lower prices and even more incentives for developers to start additional projects.

This went on for a while without becoming an immediate problem. But this changed when a series of bad developments occurred and changed the overarching growth story. China’s demography is on a downtrend, marriage and urbanization rates are falling, and Covid-19 initiated financial troubles for a large part of the population. Demand for real estate dropped, and it became clear that millions of apartments would stay empty or wouldn’t even be finished.

Unsurprisingly, a large part of the debt, with which all of these projects were financed, won’t be paid back. This caused a big credit crunch, and more than half(!) of China’s former top 50 developers have gone into default.

All of these developments are slowing down growth for China in the years ahead. However, we’ve seen similar crises in other countries before. The narrative about this one is that China will experience a “Japan-like” depression and that times of rapid growth and the overall success story are now over.

I think this comparison is lacking on multiple fronts. The circumstances and challenges are different. First, Japan did not only have a property bubble but an asset bubble that included all types of assets equally. Secondly, prices were much higher than in today’s China. Especially if you look at private and public company valuations. China’s equities are everything but overvalued. You pay some of the lowest prices ever.

Another essential point is, who owes to whom? In 1990s Japan, the whole economy was intertwined. Banks owned the shares of companies, and companies the shares of banks. This led to a complete breakdown of Japan’s economy since there was a spiral of defaults and decreasing values. Basically, the balance sheet of the whole country came down as one.

This isn’t the case in today’s China. Corporate China and financial China are a lot less intertwined. Debt in one industry will not affect other industries as much.

In fact, large, publicly listed Chinese companies actively deleveraged their balance sheets for decades. Xi Jinping and his government made clear that they do not want highly leveraged companies, and thus regulators pushed to cut the debt levels of companies.

This doesn’t mean that the debt problem of China will be easy to solve or won’t lead to further problems, it just means that the Japan comparison, and with that, the eternal end of growth seems more than unlikely.

2. Consumer Sentiment, A Slow Economy and Deflation

There’s also the story of a bad sentiment within China, of course, connected to a slow economic recovery after COVID-19 and the danger of deflation. But also in terms of politics and Xi’s decisions and policies in recent years.

Now, it would be delusional to think that I can grasp the sentiment of the Chinese population. Especially in a political sense. Thus, I will not speculate about this. The historical observation, however, is that once economic troubles are solved, the sentiment usually improves, which will probably hold true here too.

Now, what I can do, is look at the data and assess whether we can see this alleged discontent and whether we are likely to see a further spiral of deflation or not.

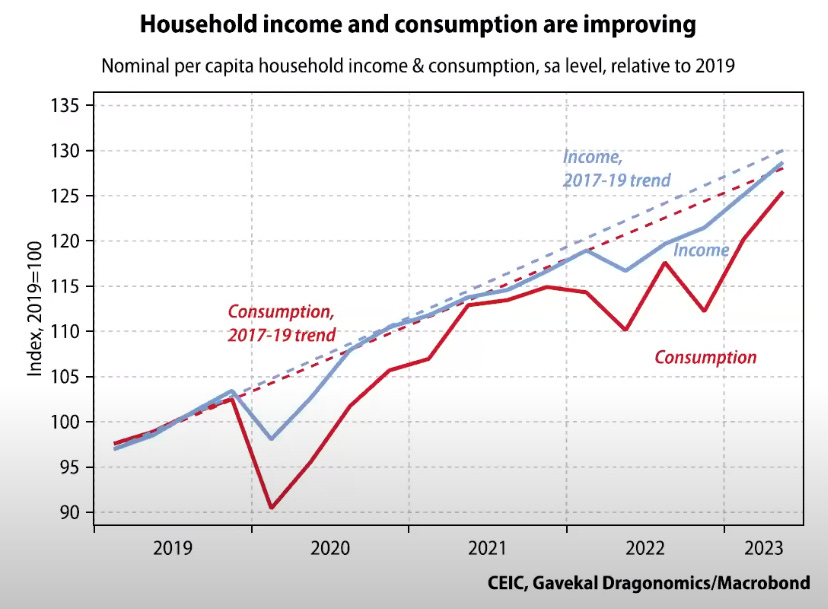

What we see here is that the pandemic and the two resulting lockdowns in 2020 and 2022 did hurt the Chinese consumer, and the government, in contrast to Western governments, did not step in. There were no stimulus checks or other forms of help.

If you consider the outrage in Europe and the US regarding the COVID policy despite stimulus packages and other policies to help consumers and businesses, imagine how Chinese consumers and business owners felt without any government support at all. It’s not surprising, that the sentiment towards the government and Xi is not at all-time highs.

But the second, more important takeaway from this is the comeback of both income and consumption. With consumption coming back even stronger than income which will eventually result in a lower savings rate.

Consumption in the latest quarter grew 8.4%, which is a lot stronger than the nominal GDP growth of 5.4%. This indicates that the consumer’s sentiment can’t be as bad as the narrative suggests, and bad consumer sentiment doesn’t seem to be what’s causing a deflationary environment. It’s more a problem of global economic weakness and thus fewer exports, as well as the debt problem. Those points are the driving deflationary powers.

This can already be seen when we look at imports. In the first seven months of 2023, imports into China declined by almost 8%. This fed into the narrative that domestic demand is low. But if we take a closer look at the numbers, we see that’s not the case. In fact, it’s once again the global downtrend that is causing the decline, since the 8% drop is due to the import prices, not domestic demand. The volume of imports was actually growing by 1%.

In the first half of 2022, import volume was down 6%, so what we see is actually rising demand for imports, thus, rising domestic demand.

Since economies globally experience more growth again and consumer spending returns, there’s a good chance that China will be able to avoid further deflationary spirals.

3. The Taiwan Conflict

In recent years, and unfortunately in recent weeks, it has become clear that the German concept of "Wandel durch Handel" - change through trade - has not succeeded. Russia still declared war on Ukraine, and although Russia did not achieve its goal and lost a lot more than they’ve won with this war, it’s still possible that China will follow the example and escalate the Taiwan situation further.

And while I hope that this will not happen, I can’t say that I’m convinced it won’t. What I am sure of, however, is that the smallest problem will be my Chinese stocks when it comes to a war between China and Taiwan.

This is a conflict that has third-world war potential. Everyone would lose in such a scenario. That’s why I still consider this lose-lose scenario to be rather unlikely and not desirable for any participant.

I also believe that the media has been exaggerating this news in recent months. This conflict has been a topic since the independence of Taiwan, and it seems to only come up when China faces overall trouble.

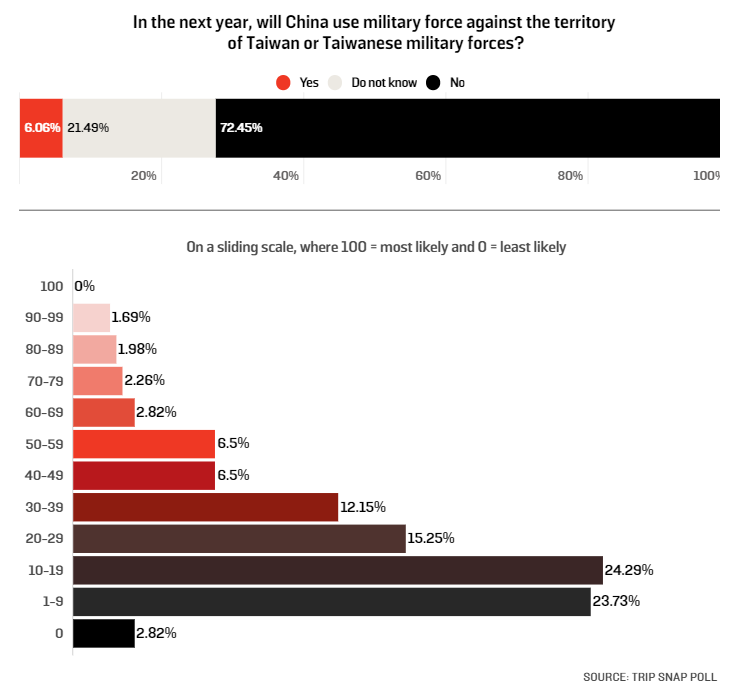

Both, the Taiwanese population, as well as experts on the field (in the study below, American international relations (IR) scholars from U.S. colleges and universities), do not believe in a military conflict, or even that the probability of such conflict has increased in recent years.

What’s also interesting, is the fact that the risk of an escalation is only priced into Chinese equities. However, what would happen to the American or global markets if such an escalation would happen? Of course, they would collapse too.

The biggest companies of the S&P 500, take Apple or Tesla as examples, benefit hugely from Chinese markets (through revenues but also production). Without China, these companies would probably be cut in half overnight. Apple produces 95% of iPhones, iPads, AirPods, and Macs in China. In addition to that, 19.2% of Apple’s revenues, over $74 billion, are made in the Chinese markets. There is no Apple without China.

So why is this risk only priced into Chinese equities? If one thinks that China will attack Taiwan, one needs to adjust U.S. positions as well. If one doesn’t think the tensions will lead to war, Chinese equities are heavily mispriced on this front.

In summary, I consider this tail risk to be overpriced in Chinese equities and underpriced in global equities. Nevertheless, this situation makes a margin of safety for Alibaba and other Chinese companies impossible. If a war breaks out (let’s hope it never will for all people involved), be prepared for your China investments to go to zero.

Summary of the Macroeconomic Risks

In summary, China is inevitable, and short-term struggles will not be the end of that. China is too important for global trade, economic growth, and the green transition to become a second Russia or Japan. And with every year that the Chinese population grows in wealth, Chinese companies grow their businesses and improve digitalization, foreign investors become less and less important to the Chinese market, which, paradoxically, will cause more foreign investors to get back into Chinese equities since the volatility and dependency of US and global investors decreases.

I don’t know when this will happen. But opinions follow trends. As soon as we start to see rising prices in Chinese markets, investors will follow. That’s how it works. In the last decade, we’ve seen a narrative switch regarding China about every three years. If that’s the case now, in a year or two, we will read about a thriving Chinese economy again. However, this time there are actual macroeconomic struggles, thus, I believe we would need a real catalyst to get out of this negativity around China.

What such a catalyst could be, will be discussed later on.

Alibaba’s Business Ecosystem

Alibaba’s business ecosystem is complex. They have numerous operations in all kinds of fields. This is typical for the market-leading companies in China. Leading US tech companies also expand into different markets, but Chinese companies tend to be even more aggressive at that.

To better structure its operations, Alibaba decided to spin off all businesses into six business units, each with its own CEO and board of directors. The six divisions are the Taobao TMALL Commerce Group, Cloud Intelligence Group, Global Digital Commerce Group, Local Services Group, Cainiao Smart Logistics, Digital Media and Entertainment Group.

Taobao TMALL Commerce Group:

The Taobao Tmall Commerce Group covers Alibaba's domestic e-commerce marketplaces and replaces the China commerce section. Taobao and Tmall make up half of Alibaba's total revenue and are China's two dominant e-commerce marketplaces.

The CEO of this part of the business is Trudy Dai. She was a member of the founding team of Alibaba and has led the Chinese commerce team since the end of 2021.

Later in this article, we will take a closer look at the Taobao and Tmall business.

The Cloud Intelligence Group:

The Cloud Intelligence Group will house the cloud business Alibaba Cloud, the communication service Ding Talk, and the AI applications/platforms of Alibaba.

In September of this year, Alibaba surprisingly announced that the former Alibaba CEO, and, at that time, the CEO of this Cloud segment Daniel Zhang, stepped down from his role and will be only active as an advisor in the future.

Eddie Wu Yongming, chairman of Taobao & Tmall Group, will succeed Zhang as CEO. This came as a surprise, and the reasons are unknown yet.

However, now it’s up to Eddi Wu Yongming to bring Alibaba Cloud back to its golden days of rapid growth. In recent quarters, Alibaba Cloud has struggled and barely grown at all. In the last quarter, they grew slowly at 4%.

But, just as we will do with the Taobao and Tmall group, we will dive deeper into the cloud market later in this article.

Global Digital Commerce Group:

Alibaba's Global Digital Commerce Group replaced the International Commerce section and includes its overseas commerce marketplaces, such as Lazada, with a main customer base in Southeast Asia, and AliExpress, which has become popular in Russia, Latin America, and parts of Europe. Trendyol, which is Alibaba’s e-commerce business focused on Turkey, and Alibaba.com are also part of this operation.

The group's CEO is Jiang Fan, who has been leading Alibaba's international e-commerce businesses since December 2021. Jiang previously oversaw the Taobao and Tmall business.

Local Services Group:

The Local Services Group replaces the Local Consumer Services division and includes food and grocery delivery services such as Alibaba's Ele.me app as well as Amap, which is Alibaba’s mapping app and a Chinese equivalent to Google Maps.

The unit's CEO is Yu Yongfu. Prior, Yongfu served as chairman and chief executive officer of Alibaba’s Digital Media and Entertainment Group and, before that, as president of Alimama, the digital marketing arm of Alibaba.

Cainiao Smart Logistics:

Cainiao is Alibaba’s logistics arm, although it also serves third-party customers. Cainiao is supposed to be the first IPO in Alibaba’s efforts to split its business into six separate units. Its revenue rose 34% in the three months to the end of June compared with the same period in 2022.

The company’s plan is to sell $1 billion in shares. Alibaba will remain the majority shareholder of Cainiao, though it will reduce its current 70% stake to a 50% holding.

The current CEO, Wan Lin, will continue as CEO after the spin-off.

Digital Media and Entertainment Group:

This section will be the home to Alibaba’s film studio Alibaba Pictures and video streaming service and the Chinese equivalent of YouTube, Youku.

Its CEO will be Fan Luyuan, who previously served as CEO of Alibaba Pictures.

Alibaba’s Financials

Now that we have a short overview of the different businesses that Alibaba consists of, let’s discuss Alibaba’s overall financials, followed by the financial importance of each segment to Alibaba.

Alibaba has grown revenues rapidly in the last seven to eight years (blue columns). From 2016 to now, the average annual growth rate of revenues was a little above 37%.

The times of high double-digit growth are over, however. Thus the average of recent years is more important to us. Starting in 2019, we get an average annual growth rate of revenues of 30%. Still very impressive.

The bad sentiment about Alibaba’s growth started in 2022 when revenue growth declined steeply, as can be seen in the quarterly results. In 2022, Alibaba only grew in the low single digits.

The last reported quarter showed stronger growth again, and it seems as if Alibaba can slowly outgrow the weak quarters of recent years. Despite the still struggling overall economy in China.

Looking at the operating income, we can also see the hit that Alibaba’s business took. Operating income declined by about 9% from 2021 to 2022 due to lower operating margins and less demand caused by the weak Chinese economy and the Chinese consumer saving more money.

As mentioned above, however, the most recent quarterly results (ended in June) showed that growth is back with overall revenue growth of 14%, a growing core business (Taobao and Tmall Group), and other operations growing +30% and arriving at profitability.

This is in line with our observations, that the Chinese consumer is starting to spend again, and savings rates coming down. The next quarterly earnings will be interesting to see if this is an ongoing trend or just a short-term recovery. I’ll deliver updates when earnings come out or general news reports on the Chinese consumer.

Balance Sheet

Let’s take a look at the most important aspects of Alibaba’s balance sheet.

Alibaba sits on a huge pile of cash and short-term assets. The current cash position is about $31 billion, and cash and short-term assets combined amount to $75 billion. Considering the $52 billion in current liabilities, there are no worries about Alibaba’s short-term liquidity.

The same can be said about the long-term outlook of the business. With long-term debt of $21 billion, Alibaba could pay those debts in cash at any given time.

Additionally, Alibaba has retained earnings of almost 87$ billion. Because of this huge amount of cash that Alibaba holds and the low price the stock trades at, Alibaba has authorized a stock buyback program of $25 billion. Which is a good sign. Not only because buybacks increase one’s share in the business but also because it shows that the management allocates its capital well.

At a stock price of $82, that would result in over 300 million bought-back shares. Currently outstanding are about $2.5 billion, which would mean that they buy back approximately 12% of outstanding shares, which would be extremely bullish for Alibaba.

However, if we look at the history of Alibaba’s share buyback programs, we will realize that Alibaba has announced buyback programs of $10b and more before, and they have never used all those funds. Historically, they used less than half of the authorized capital.

If we take a look at the outstanding shares since 2017, we see that the amount was pretty much stable. The shares they bought back, only balanced out the dilution happening at the same time.

If this goes on, shareholders will see little value from it.

Recent Results and Individual Performance of Each Segment

Let’s take a look at the most recent results and the individual performance of each segment.

Taobao and Tmall Group:

Alibaba’s most important business segment, with ~46% of revenues in the quarter, was able to grow 12% YoY and was by far the most profitable part of the business, being responsible for 108(!)% of adj. EBITA in the quarter, meaning that it not only is the most profitable business, it also sort of subsidies the still loss-making operations of Alibaba.

The EBITA margin was at 43%, only slightly lower than last quarter at 44%.

Direct sales and others recorded the strongest YoY growth, with 21%. According to Alibaba’s earnings report, primarily driven by the consumer electronics category.

International Digital Commerce Group:

This segment reported stellar growth of 41% YoY, driven by 60% growth in international commerce retail. AliExpress delivered robust order growth and an improved user retention rate and purchase frequency.

Lazada and Trendyol both improved their margins, and Trendyol achieved its first-ever positive operating result. Both businesses were able to scale and should see further improvement in margins and unit economics. Unfortunately, Alibaba didn’t report exact numbers for the margins.

The overall segment is still not profitable yet, but it’s getting very close. The EBITA margin improved from negative 9% to negative 2% resulting in a loss of 420mn RMB compared to 1,380mn RMB a year ago.

The International Digital Commerce Group was responsible for ~9% of revenues.

Local Services Group:

The Local Services Group also reported significant growth at 30% YoY. Primarily driven by the growth of Ele.me and Amap. Nevertheless, this segment is still heavily loss-making, with an EBITA margin of negative 14%. While that sounds bad, it was an extensive improvement to the year prior, where the EBITA margin was a negative 25%.

Currently, this segment is responsible for a little less than 6% of revenues.

Cainiao Smart Logistics Network:

The Cainiao segment is out of the red for the first time as it reports adj. EBITA results of 877Mn RMB compared to negative 185Mn RMB last year. The EBITA margin improved from negative 4% to a positive 1% while growing revenues at 34% YoY.

The growth was primarily driven by an increase in international fulfillment solution services and domestic consumer logistics services. In 2023, Cainiao also launched its “5-Day Global Delivery” service/promise and commenced the operation of three new international sorting centers, bringing the number of overseas sorting centers in operation to 18.

The logistic arm contributed 8.6% to Alibaba’s revenues.

Cloud Intelligence Group:

Alibaba’s cloud business disappoints once again. Having grown by 50% annually a couple of years back, cloud growth has been weak in post-pandemic years, showing another quarter of slow growth, 4% YoY.

Gaining back momentum in the Cloud business would be a strong catalyst for Alibaba, considering it’s responsible for more than 10% of revenues and should’ve lots of room to grow. We will discuss the Cloud opportunity later in more detail.

Adj. EBITA showed strong growth of 106%. Yet, this sounds better than it is, considering the reason for that improvement was cost reductions caused by less traffic, and last year’s base was pretty low. The EBITA margin is roughly 1.5%.

Digital Media and Entertainment Group:

Besides the Cainiao segment, the Digital Media and Entertainment Group also reported its first profitable quarter. Revenues grew 36% YoY, primarily driven by growth in the online entertainment business and a strong recovery of the offline entertainment business after the reopening.

The EBITA margin improved from negative 23% to a little above 1%. This segment accounted for 2.1% of revenues and is thus the smallest of all segments.

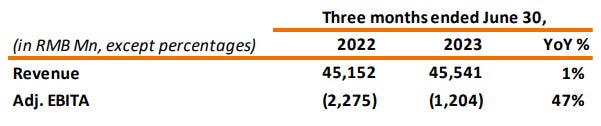

All other Segments:

The last segment is a more or less unconnected combination of Alibaba’s businesses that did not belong to any other business segment. This includes AlibabaHealth and Freshippo, which were originally part of the China e-commerce segment, which is now called the Taobao and Tmall Group, and other smaller businesses.

Although the name suggests, that this segment isn’t very relevant, it actually is, representing over 18% of revenues.

Revenue of this segment increased very slightly, with 1% YoY. The segment is still loss-making with an EBITA margin of negative 2.5%, compared to negative 5% in the same quarter last year, and a loss of 1,204Mn RMB.

We will have to wait and see what Alibaba has planned for this segment. However, I hope they bring a little more structure into it and focus on profitability and growth since 18% of revenues is nothing you should neglect.

A little more communication on future plans would be needed in the coming quarters.

Overall Revenue Breakdown (including US$):

Now, let’s dig deeper into the two most important businesses of Alibaba. The Taobao and Tmall Group and Alibaba Cloud. While the Cloud business isn’t close to the financial importance of the Taobao and Tmall Group yet, it’s the business that has the best growth opportunities. If it comes back on track…

Alibaba Cloud (Cloud Intelligence)

Before exploring Alibaba Cloud or the global cloud market, we must understand the three main types of cloud computing. Each type has its own range of services and cloud providers that make up the market. The dominant type of cloud computing also differs between regions and countries. The three main cloud computing types are:

Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS)

IaaS is an offering of cloud computing where the provider supplies you on-demand access to computing resources such as networking, storage, and servers. Within the providers’ infrastructure, you run your own platforms and applications. This provides a flexible hardware resource that can scale depending on your storage and processing needs.

Platform as a Service (PaaS):

PaaS is an offering of cloud computing where the provider gives you access to a cloud environment in which to develop, manage, and host applications. You will have access to a range of tools through the platform to support testing and development.

The provider is responsible for the underlying infrastructure, security, operating systems, and backups.

Software as a Service (SaaS)

SaaS is an offering of cloud computing where the provider gives you access to their cloud-based software. Instead of installing the software application on your local device, you access the provider’s application using the web or an API.

Through the application, you store and analyze your own data. You don’t have to invest time in installing, managing, or upgrading software, this is all handled by the provider. (Source of Definitions: Kinsta)

Let’s take a look the the global cloud market now and then work toward the Chinese cloud market and, eventually, Alibaba and its competitors.

The Cloud Market Opportunity

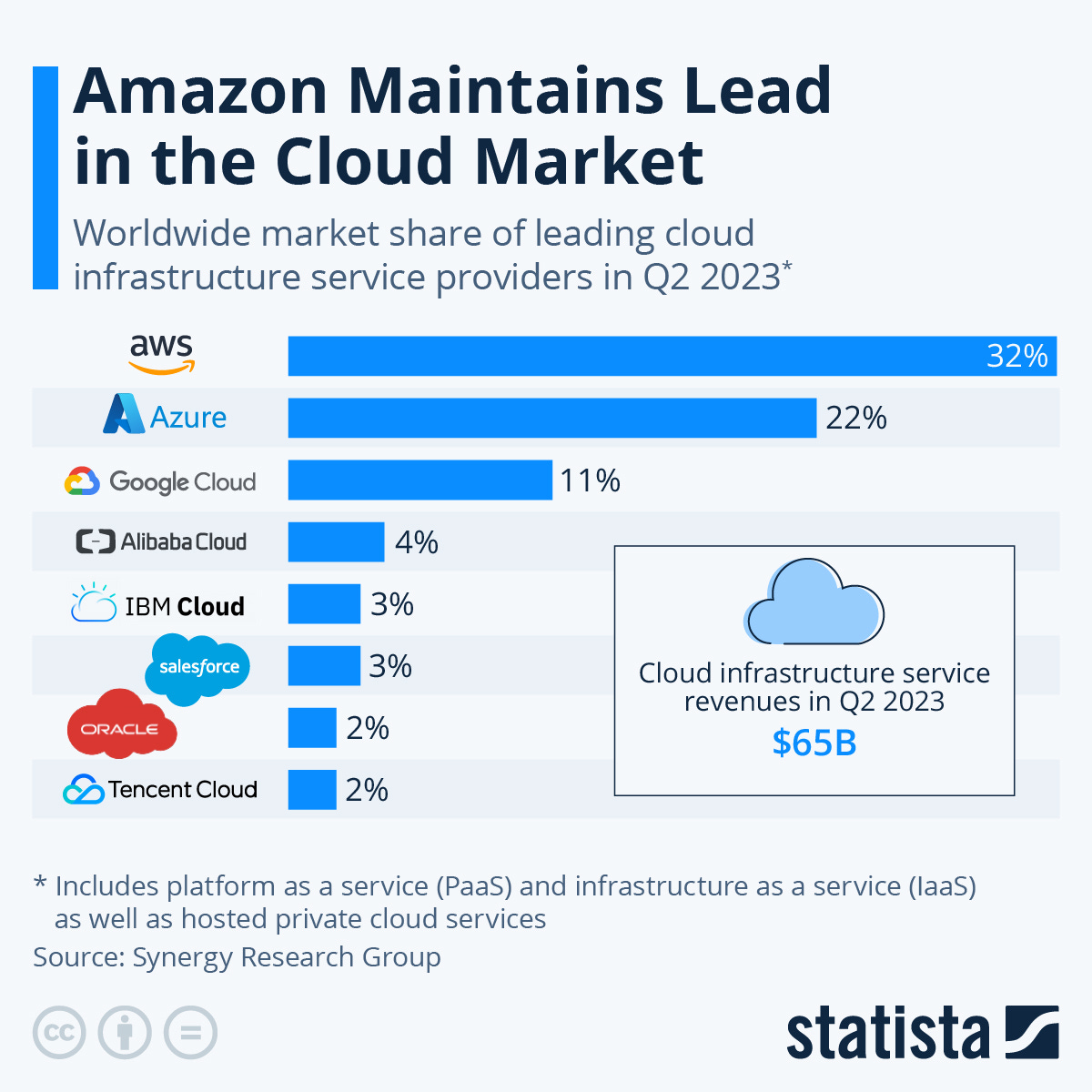

Looking at the trailing twelve months, the cloud market is a +$250 billion opportunity and expected to grow between 15%-18% annually. Considering these numbers, it’s no surprise that every big tech player wants a share of this market.

Currently, the five biggest players are AWS (Amazon), Azure (Microsoft), Google Cloud, Alibaba Cloud, and IBM Cloud. 65% of the market are dominated by the top three. Alibaba Cloud, as the only non-American player, has a global market share of 4% and is (currently) growing significantly slower than its American counterparts.

How important cloud growth is to investors was also shown last week after the results of Google (Alphabet) came out. They reported a great quarter, however, the stock plunged 10% afterward since they slightly missed the growth expectations of their cloud segment. In the cloud market, it’s extremely important to gain a spot at the top. It’s a typical “ the winner-takes-it-all market.”

Once companies decide to use a certain cloud and train their employees with it, switching it is costly and, therefore, unlikely. Thus, gaining market share now, when the market is still growing rapidly, is important. Even worse is Alibaba’s setback in the last two years. However, Alibaba Cloud has some tailwinds that give it another chance to get back to old growth rates beyond 30% annually.

Cloud in China

First, China doesn’t want US cloud providers in their national market. AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud will not be able to grow as fast in China as they do in other parts of the world.

Secondly, despite the bad economic situation of the last two years, the Chinese cloud market will inevitably grow a lot faster in the future. Last year, experts predicted 25% to 28% annual growth for the Chinese cloud market, compared to the 15%-18% outside of China. Since this growth wasn’t achieved in 2023, even more rapid growth, around 30%, is expected when the Chinese economy comes back.

China has the largest online population in the world and is eager to come out on top of new technologies and innovations. A current example are electric vehicles. China is now the biggest exporter of EVs in the world.

They have similar ambitions with Cloud computing and are already expanding into countries in Africa, South America, and Europe. In China’s 14th Five-Year Plan, the development of Cloud Computing was declared a national priority.

Alibaba Cloud has a market share of 39% in China. It actually increased from 34% in recent years, although there’s a long-term downtrend when we compare today’s number with six to seven years ago. Following Alibaba is Huawei cloud, with a market share of 19% and the strongest YoY growth from all competitors, with 14%. Third on the list is Tencent Cloud, with a market share of 15%.

Differences between the US and Chinese Cloud Market

The biggest difference between the US cloud market and the Chinese cloud market is in its composition. Remember when we talked about IaaS, PaaS, and SaaS?

SaaS and PaaS jointly account for roughly 80% of the public US cloud market, but only 26% of the Chinese cloud market. The problem for Chinese cloud providers is that SaaS offers the highest margins. And, currently, IaaS is still growing in the Chinese market.

Why is that, and will this trend reverse in the future?

SaaS services are primarily addressed to medium-sized companies in the beginning. After high adoption in that field, you can start marketing these services to the larger operations. But there’s a problem with that in China.

1. Digitalization of Records

In the US, the order in which companies digitalized looked something like this: Paper records → Documents saved online → Turned into Data → Complex IT systems (by Microsoft, IBM, Oracle, and SAP) → Cloud applications.

In China, however, many companies, especially small and mid-sized ones, are still storing their documents in paper form or online without accessibility or further use to the typical employee. The next step would be the introduction of IT systems. Instead, introducing IT systems and cloud applications happens parallel in China.

While this makes it more difficult, it could mean that the timeframe between implementing IT systems and cloud services will be faster than it was in the US. Some companies will go straight to the cloud.

2. Costs (Especially Labor Costs)

Historically, cheap labor in China has meant that performing most tasks manually is still cost-effective. The Chinese medium-sized companies that want to integrate cloud or already have, prefer to make one-off or up-front payments to capitalize IT and software costs instead of choosing recurring-cost models. This has slowed down SaaS growth in China.

For this reason, I think that we will not see the same margins of cloud businesses in China in the next few years. However, a transition to a more SaaS-oriented cloud should be the natural development as the west-east wage gap is closing fast in recent years.

In the graph, you see absolute income growth (black line) and the growth rates of wages (blue columns).

3. Small and Medium-Sized Companies are Young

According to Professor Li Jianwei from the China University of Political Science and Law, the average lifespan of Chinese private companies is about three years (2.9). These numbers are from 2011 but are still relevant, considering that changes in such numbers happen over the course of many years.

There are no precise numbers that I’ve found for American companies since it’s not clear what “medium-sized” means in detail. However, American companies seem to last at least twice as long.

Younger firms, that focus on surviving the first years, tend to prioritize spending on marketing and secure reliable revenue streams. They don’t take the risk of recurring payments for software that’s not directly improving their financials.

To support these small and medium-sized businesses, the Chinese government started the “little giants” program oriented on the German concept of “Hidden Champions.” Medium-sized companies that drive innovation and digitalization.

These efforts could increase the life span of companies and create incentives to invest in software and cloud services.

4. The Private Cloud

The private cloud is still a substantial part of the cloud market in China. In 2021, private cloud accounted for about a third of China’s overall cloud market, and it is expected to increase to over 40% by 2025.

The high share of private cloud slows down growth and profitability for cloud providers. Most companies prefer the private cloud because of security doubts and a tendency to keep data in-house, especially companies that operate in a regulated sector such as financial services.

Contrary to some of the other differences that I listed here, I don’t think this trend will reverse. Regulation is stricter in China, and companies will pay more attention to the safety of data and keeping sole control over it.

Conclusion on Cloud

The weak growth of Alibaba’s cloud businesses was my biggest concern about Alibaba’s business. It was meant to be the number one driver of growth for years to come and ended up underperforming quarter after quarter.

However, after analyzing the sector, my views have changed, and it seems that these problems were heavily dependent on the overall state of the Chinese economy and the health of medium-sized companies. This will reverse in the next years when China’s economy gets back on track.

Still, Huawei Cloud was able to achieve double-digit growth in the last quarters and is slowly closing the gap with Alibaba Cloud. So there definitely are problems within Alibaba Cloud that are not part of the macroeconomic environment.

This can also be seen in the change of Alibaba Cloud’s CEO. Daniel Zang stepping down as CEO of the cloud business was a surprise to everyone and details of that decision are still unknown. But since we don’t know anything about the reasons, speculating isn’t helpful here. It could be related to the business, it could be something personal, we don’t know. Since he remains in the company in an advisory role, we have to assume nothing too bad happened, and it was an amicable solution.

I’ll take a close look at the coming quarters regarding Alibaba Cloud, especially since this is one of the main catalysts for Alibaba business-wise. If cloud growth comes back, Alibaba stock has room to recover.

The Taobao and Tmall Group

As we’ve seen in the discussion of revenue per segment, Taobao and Tmall are the life insurance of Alibaba. Over 49% of revenues in the last quarter and 108% of EBITA margin, thereby literally subsidizing other loss-making operations.

Taobao is a C2C (Customer-to-Customer) marketplace, while Tmall is a B2C (Business-to-Customer) marketplace. Alibaba first launched Taobao, in 2003, and later on Tmall, in 2008, to expand its offerings to more premium products. Since C2C platforms, like eBay or Etsy in the West, are better known for cheap prices than high quality.

Taobao and Tmall are closely linked because Tmall was originally launched as a subsidiary of Taobao to benefit from the reach and logistics that the Taobao business has built up.

By now, both marketplaces are almost equally strong and two of the three biggest in the world. The only non-Chinese e-commerce platform in the global top 5 is Amazon. And, for now, it’s also the leading one. At least if we consider Taobao and Tmall separate businesses and don’t combine them under the umbrella of Alibaba.

However, it’s likely that this gap will close very soon. 48% of future e-commerce growth will come from the Asia-Pacific region, where Chinese retailers are the dominant players. India is an exception, though. Amazon still holds the number 1 spot there, followed by Indian e-commerce platform Flipkart and only then Alibaba.

In 2022, five countries from Southeast Asia made the top of the list for fastest e-commerce growth:

Philippines (24.1%)

India (22.3%)

Indonesia (20%)

Malaysia (18%)

Thailand (16%)

While Alibaba is the biggest e-commerce platform in China, with almost 50% of the total market share, it is planning on expanding its business. Not only across Asia but also in Europe.

A market mostly dominated by Amazon. It’s a smart move since Chinese e-commerce growth rates are slowly coming down from the outstanding numbers since 2017.

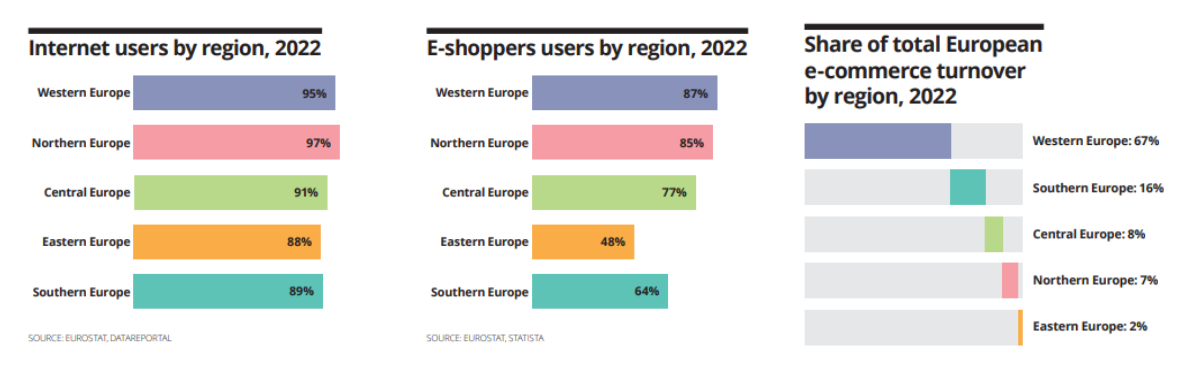

Europe’s projected e-commerce sales growth is strong and could mean a new opportunity for Alibaba to diversify its operations and differentiate from its Chinese competitors.

This graphic shows the strong growth of European e-commerce in global comparison. Although we shouldn’t neglect, that Europe’s base is much smaller than the Asian and North American base. Also, because of China’s size in absolute numbers, they “pull down” the Asian growth a little bit. As I mentioned above, the five fastest-growing e-commerce markets are all from Southeast Asia.

The success of Alibaba’s expansion into Europe depends on different factors. In the past, Alibaba tried to expand into the European market with AliExpress, but they couldn’t sustainably build market share because of long shipping times, fiscal measures imposed by European policymakers, and not being attractive enough to European consumers.

The new tactic is a more local focus on each individual country and culture. A pilot project started in Spain in June of 2023.

In my opinion, as a European, this is a much more promising way than the prior AliExpress ambitions. Yet, I still think they’ll have a tough time in many of the Western European countries that are dominated by Amazon and not necessarily keen to switch to a Chinese alternative. The success will depend on Alibaba’s ability to adapt to the European consumer and especially on gaining market share in Southern, Eastern, and Central Europe.

These markets have more runway for future growth, and consumers care less about buying goods from China and more about prices.

In Eastern Europe, the percentage of shoppers who bought goods online has more than doubled in the last five years. In Southern Europe, that number grew by 17%. These are markets that Alibaba has the best chance to build significant market share.

In Western Europe, it is all about marketing and how the perception of customers will be. The local concept is the right approach, but we still have to see whether it can be successful or not.

In Turkey, another important and growing market (expected growth of 13.6% annually from 2023-2027), Alibaba has already gained significant market share through its platform Trendyol. It’s the second biggest e-commerce platform in Turkey, with a 25% market share.

Conclusion on Taobao and Tmall:

Taobao and Tmall are Alibaba’s most important businesses, and it’ll likely stay that way for a while. In the last quarter, this segment showed growth of 14% which is a very good result.

In the future, the Chinese part of the business will likely grow in line with the general Chinese e-commerce market, which would result in growth of about 12-13%. Depending on their expansion success, this growth rate could be slightly increased by operations in Europe and other parts of Asia.

Personal Fit and Risk

Now that we’ve discussed China’s macroeconomic outlook and Alibaba’s business and financials, let’s conclude what an investment in Alibaba means and who should consider it.

Personally, I believe this investment is primarily about personal fit.

Risk Tolerance:

You need to be able to take the risk and its consequences. Risk is nothing theoretical! Risk means, that if things go south the way I outlined in this analysis multiple times, your money can be gone!

Position Sizing:

Because of the risk the unlimited downside risk when tail risks occur, I believe that age matters a lot. If you’re young, you should think more in absolute than relative terms about your investments. If you only have $1000 invested, it doesn’t make much sense, in my opinion, to think about percentages.

You have so much earnings power in the future, that you can take higher risk bets. If you lose $200, that’s not a nice thing, but it’s a very small loss compared to your future capital inflows. If the investment simultaneously offers a 5x, it’s worth the risk.

If you have less earnings power in the future, position sizing in relative terms matters more. You should only build a position that you are truly willing to risk high losses on!

My reasons for being invested:

I’m invested in Alibaba for two simple reasons.

The business has very strong financials and a market-leading position in the fastest-growing and biggest industries in a (still) fast-growing economy. And I can buy all of that at a ridiculously low valuation.

Secondly, China’s position in the global economy is different from every other country that ran into similar problems before. China is not Japan, and it is not Russia. The global dependency on China is huge, making the bargaining power of China powerful, both politically and economically.

Earlier in this analysis, I wrote that China is inevitable. And I think that’s the case. With this inevitability, a recovery of its economy and its biggest and highest-quality companies will occur sooner or later. Although I believe it’s a possibility that it’ll take two or three years until all the dust settles.

Catalysts

Let’s discuss some catalysts. I’ve mentioned most of them throughout this article already, so let’s recap and summarize them.

There are two types of catalysts. Category one are the catalysts on the microeconomic level. Things that can improve in Alibaba’s businesses and thus restore faith in the future prospects of the company. I consider Alibaba’s cloud to be the number one catalyst of this category.

Alibaba Cloud was the most disappointing segment in recent quarters and underperformed the expectations of investors heavily. This was also the part of the business that worried me the most. While Taobao and Tmall are great businesses, Alibaba Cloud is the promise for the future growth of Alibaba. The opportunity is huge, and Alibaba’s position in this market should make them the biggest beneficiary.

After researching the Chinese cloud business and comparing it to the global cloud market, I’m confident, however, that Alibaba Cloud will recover and get back to double-digit growth eventually. When that will happen is hard to say. It depends on the recovery of China’s economy and, thereby, the willingness to pay and the general financial strength of medium-sized Chinese companies. Growth-wise, Alibaba Cloud might be in AWS’s position from 2016 to 2017.

Other catalysts on the business side have little impact on Alibaba’s stock performance. Some other business segments hitting profitability would be a great signal for Alibaba, but investors wouldn’t care much at the moment, and it wouldn’t move the needle on Alibaba’s financials.

The second category, and much more important, are the macroeconomic catalysts. China’s economy must overcome the problems I’ve discussed in this article. That will be the start of another bull cycle for China. This can take time. But due to the reasons I have outlined, I’m confident that it will happen.

A short-term catalyst would be a stimulus package from the Chinese government. US investors have been waiting for such an announcement for months, and Xi and the Chinese government are slowly leaning in that direction after months of small policy changes that didn’t really solve any of the underlying bigger problems. But once again, I don’t know when or if we’ll see a final commitment to these plans.

Valuation

This analysis is very much focused on macroeconomics. That’s the complete opposite of my usual approach, but in this case, I thought this offers the most value to you as the reader since macroeconomics is the main reason for the downtrend of Alibaba and Chinese equity in general.

In the following valuation models, you’ll see that there is no debate that, business-wise, Alibaba’s valuation can only be considered a bargain.

Today, we’ll discuss a Discounted Cash Flow Analysis and a Reversed Cash Flow Analysis. I also considered performing a Sum-of-the-Parts model since this would be reasonable to do after the announcement of the split up of Alibaba’s businesses.

However, I’ll include a sum-of-the-parts valuation model in the upcoming articles when I research the smaller business segments individually.

Discounted Cash-Flow Model:

Well, as you can see, Alibaba’s valuation is extremely undervalued if we look at the relationship of expected future cash flows to the current price level.

However, I’ve already discussed the flaws of DCFs and the high range of possible outcomes based on your assumptions in my Visa Deep Dive. The results we got here seem rather optimistic, although my assumptions were conservative, in my opinion. You’ll see in the reversed cash flow model that it comes up with lower numbers than the DCF.

Let’s discuss the three cases:

Base Case: In the base case scenario, I expect growth of 9% over the complete 10-year period. Because of China’s current problems, I would expect the next two to three years to be lower than that. After a recovery of the Chinese economy, however, I expect Alibaba to grow faster again, averaging 9% growth.

Due to the uncertainty of when exactly China’s economy will get back on its feet, I chose to go with 9% as the average for the whole 10-year period. I’ve applied a multiple of 14.

The historical P/E ratio, as seen in the chart, was a lot higher, but I want to be conservative here and adjust for the fact that it’s possible that foreign investors won’t return as fast as I might think. Still, with the buyback program alone, Alibaba has lots of ammunition to achieve this P/E easily. (If they actually use their buyback authorizations this time)

With these assumptions, we come to a fair/intrinsic value of $347.70, representing an upside of almost 360%. By the way, all of this while I use my usual 15% discount rate, which is a high hurdle rate.

Best Case: In the best case scenario, Alibaba Cloud delivers on its promises and returns to high double-digit growth. China’s tensions with the US ease, and foreign investments in China rise again.

Based on these assumptions, the multiple would improve to 18 easily, and Alibaba’s growth would bounce back to the mid-teens and eventually low double digits.

I know this seems like a stretch to many, considering the current situation. But I don’t think this is unrealistic. From a business perspective, I consider this to be more realistic than the worst-case scenario.

Worst Case: In my worst-case scenario, I basically assume that everything currently said in the media turns out true. China’s growth is over and will not recover. GDP growth will slowly decrease and approach two to three percent per year. Alibaba only performs slightly better or right in line with GDP growth, and investments basically completely stop leading to a terminal multiple of 7 only driven by buybacks.

The crazy thing, even if that happens, and I highly doubt it, Alibaba has an upside potential of 138% according to this model. As I said, business-wise, Alibaba’s margin of safety is enormous.

Yet, I’ll say it one last time since this is the worst-case scenario, there is no margin of safety in terms of global conflicts that might escalate.

Reversed Cash Flow Analysis:

My reversed cash flow analysis shows that current market participants are pretty much exactly pricing Alibaba for the worst-case scenario of my DCF model. Alibaba is currently priced for 3.5% annual growth in the next ten years.

That would literally mean that Alibaba is growing slower than the expectations for China’s GDP. This is pretty much impossible. If China’s economy doesn’t collapse completely, Alibaba will outperform the overall economy by multiples of 3x, with exuberance in markets and the cloud reaching its potential closer to 4x.

If we assume the base case growth of 9%, the reverse model would come up with an intrinsic value of $119, resulting in an upside potential to fair value of 45%. Still impressive, but much lower than our DCF prediction. The reason for this extreme difference lies in the Terminal multiple of the DCF model compared to the Terminal growth rate used in the reversed cash flow approach.

I feel like the margin of safety lies somewhere in the middle of 45% and 138%. All these models can give you, are estimations. You shouldn’t put too much weight on the exact numbers.

Extra Note:

Initially, I planned this Deep Dive to be more focused on Alibaba’s business. But the more I researched, the more I realized that there are a lot more questions regarding China than Alibaba’s business ventures.

So I decided to focus on the most important parts of Alibaba’s business and then discuss the most crucial worries in regards to China and its economy.

Over the next few weeks, I’ll write shorter deep dives into each business segment of Alibaba (5-minute breakdowns) for everyone further interested in the business of Alibaba.

I’m also already writing the next deep dive that will be published earlier than usual, so you don’t have to wait so long. This time, it’s about a medium-sized Italian company that I just recently built a position in. Paid Subscribers already know about that ;)

Deep Dives like these take a lot of time to research and write. But I love it, and I believe it is very valuable content that helps anyone who wants to learn about businesses and investing.

If you want access to these monthly deep dives and more research content, consider becoming a Paid Subscriber:

Here are all the tools that I use for researching Companies/Stocks:

My Current Portfolio:

My Last Deep Dive:

And my Investing Checklist System ($1.99 instead of $4.99 today):

https://danielmnkeproducts.com/

Disclaimer:

I’m not a financial advisor, and this is not financial advice. This article is for research purposes only. You have to make your own investment decisions based on your research and individual situation.

Thanks for reading, and have a great day!