Streaming Sector Analysis - Who Will Win the Streaming War?

"Welcome to the Streaming Wars!" This Deep Dive delves into the fierce competition among major players in the Streaming Sector. Who will win the War and become the King of Streaming?

Content:

Introduction

The Sector/Industry

Overview

Streaming War Phase 1

The Value Proposition

Subscriber Growth at All Costs

Streaming War Phase 2

Profitability

Ad-Supported Subscriptions

Bundles and M&A

The Key Players

Netflix

Average Revenue by Membership

Net Additions (Losses) of Memberships

Membership Retention Rates

Disney+

Metric Comparison

Consumer Perspective

Conclusion

Prime Video

Introduction Prime Ecosystem

Prime Video Strategy

Consumer Perspective

YouTube

Role in the Streaming Market

YouTube Premium

Consumer Perspective

Max

Introduction

Comparing Numbers and Strategy

Investing in Streaming Companies

Introduction

The streaming sector is a unique and interesting sector that I wanted to write about for a long time. First, because I deal with it on a (more or less…) daily basis as a consumer, and second, because it has some really interesting business aspects.

Somewhere in the late 2010s, the streaming hype broke loose, and seemingly every production company, TV channel, and tech company introduced a streaming service.

Everyone felt like this was a market they needed to be a part of. Fast forward a couple of years, and there are some serious doubts about whether the market is actually a great place to be in.

The term “Streaming War” is now regularly used to describe the competitive nature of the industry.

Let’s start this Deep Dive with a breakdown of the industry overall, followed by an analysis of the key players in the industry.

The Industry

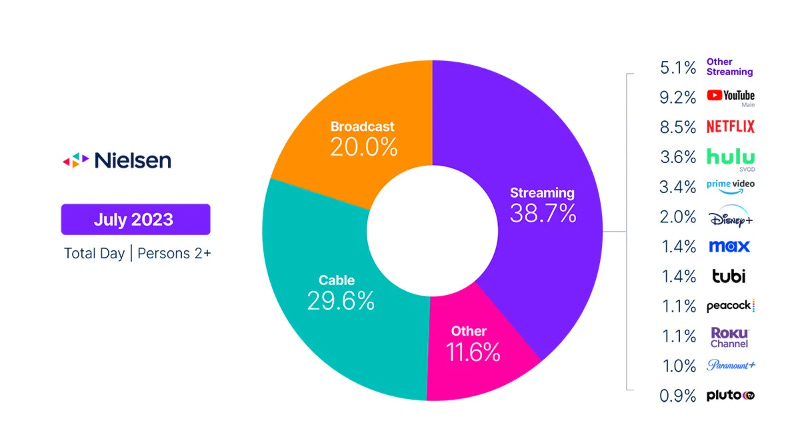

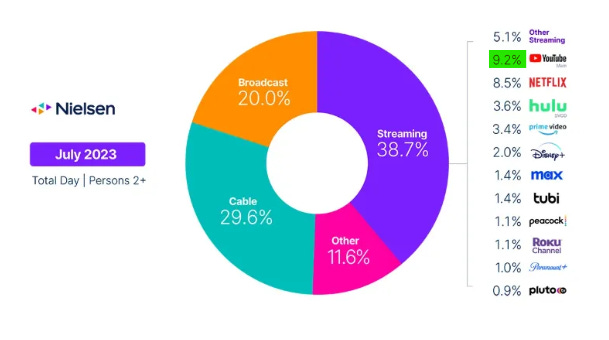

After revolutionizing other entertainment industries like music or books, Silicon Valley has now also disrupted the movie industry. Almost 40% of US TV consumption is watched over streaming accounts.

And everything indicates that this trend will continue and even accelerate. Almost every household with a TV also owns devices to watch streaming services.

In fact, young people below 35 have more than halved their average minutes of TV per day over the last ten years. And the decline of Broadcast and Cable has accelerated quickly in recent years.

The video streaming market is currently valued between $100-$120 billion and is expected to grow at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 20-22% up until 2030. This could result in a value of roughly half a trillion dollars in 2030. However, estimates on this market are highly volatile, and as we will see throughout this article, not even the companies themselves really know what they can expect. Both in terms of subscriber growth and profitability.

It seems that no one in the industry expected the competition to be as fierce as it is today. Let’s dive deeper into the fight for subscribers and market share.

Streaming War Phase 1

While Broadcast and cable seem to be the big losers of the streaming revolution at first glance, the individual streaming services are not as happy with the development of the industry either.

Initially joining the sector to grab their share of a fast-growing and allegedly highly profitable market, the fierce competition that evolved made both of these things challenging for the entrants. Subscriber growth wasn’t as fast and long-lasting as expected, and profitability is still far away for most services.

In recent quarters, many streaming services experienced negative subscription growth for the first time—even the big players like Netflix or Disney+. Instead of adding new subscribers, Netflix experienced stagnation and even slight negative growth throughout 2022. Disney+ lost significantly in 2023, going from 164 million paying subscribers to less than 150 million.

There are many reasons for that. The most apparent one is competition. The more services joined the industry, the more challenging it has become to keep retention rates on subscribers high. Especially since prices kept increasing.

The Original Value Proposition

Initially, streaming services had a very straightforward value proposition. For $7.99 (Netflix’s starting price), you got the newest and best shows without the annoying advertisements of standard television and on-demand. This was a revolutionizing business model with essentially zero downside for the consumer.

But this value proposition only worked as long as Netflix was the only serious contender in the market. With new services coming in, Netflix, as well as the new contenders, had to fight for subscribers. Activating your microeconomics knowledge, the natural solution should’ve been that this new competition drives prices down. However, this wasn’t the case here. Everyone quickly realized that splitting up the customers leads to less revenue for every player, and lowering prices further would’ve resulted in many quick bankruptcies.

So, companies decided to go another way. They bet on delivering more value than other services through better content. More and more money was spent, but there wasn’t anyone who triumphed and overshadowed the others in the content game. Netflix had some big releases, but so did Disney+ or HBO. It balanced out more or less.

To fund the increasing spending on content, the streaming services collectively increased prices. With regularly growing prices, the first noticeable drawdown in subscribers took place.

By this time, the price factor of the original value proposition became mostly abundant. Customers needed to be subscribed to three or four different streaming services to capture 80% of the most viewed and talked about shows. Those subscriptions could quickly add up to $50 per month.

Subscribing to streaming services was not the no-brainer it used to be—especially staying subscribed. Instead of deciding to subscribe to a streaming service and then stick with it, subscribing for a month to watch the new show you were waiting for and unsubscribing as soon as you’ve watched it became a normal way to consume streaming. This can also be seen in the user retention statistics, which we will discuss later.

This became a huge problem for companies, especially for players like Disney+, who spend record sums on producing new content. It became increasingly clear that the sole goal of gaining subscribers would not be enough to make the service successful.

Streaming War Phase 2

This is a pattern that we have seen over and over again in the online industry. First in the late 90s and early 2000s and again when the big social media companies came along.

User and subscriber growth are more important than financial growth and profitability.

Two of Netflix’s biggest competitors, Disney+ and HBO Max (now Max), wanted to gain market share at every cost and prevent Netflix from becoming the undisputable market leader. They spent billions on new content to grow their subscriber base.

In some years, Disney has outspent Netflix by almost 200%. (we will debate this further when discussing Disney+ in particular).

After the first signs of slowing subscriber growth in recent quarters and years, however, the companies understood that growing at any cost is a strategy limited by time, especially since the market might be saturated faster than they initially thought.

The total addressable market for Netflix was estimated to be around 800-900 million people. After seeing significantly lower growth at a little more than a quarter of that, I’d at least question if 900 million is a realistic number any time soon.

As a consequence, streaming services stopped competing solely for subscriber growth. They shifted their focus to becoming more profitable.

In the pursuit of becoming more profitable, almost all streaming services started to break down the password sharing that was going on between users across all platforms. While this move, naturally, was not well received by users, the companies were right, and it did the job. Some users might have stayed away from the streaming services without using a friend's password, but most created their own account, and it was a net positive for Netflix and co.

However, the two most prominent features of the second phase of the streaming wars are the bundling of services and the inclusion of ads.

Bundling of Services and M&A (Mergers and Acquisitions)

Instead of competing for customers, many streaming services now offer deals where you can access multiple services with only one subscription.

Some of these bundles are temporary; others turned into mergers and acquisitions. Especially Disney+ started buying competitors. Comcast’s Hulu was their latest and biggest acquisition. The deal valued Hulu at a total of $27.5 billion.

In April of 2023, HBO Max and Discovery+ merged and formed the new service Max. A couple of months later, in June, Paramount+ acquired Showtime.

The main reason for the mergers are larger content libraries that should increase the average subscription time by offering more shows, thus creating less reliability on the latest releases.

Ad-Supported Subscriptions

The ad-supported subscriptions were discussed for quite a while, and initially, the sentiment wasn’t positive. However, they turned out to be a great alternative, benefiting the companies and the consumer.

I personally prefer subscribing to the significantly cheaper ad-supported options.

And this seems true for many people since user growth came back strong after introducing these ad-free alternatives. Some of the initial criticism was that Netflix (who were the first to offer this alternative) would slowly become like old-school TV if they continued on this path.

But this isn’t true from both the customer and business perspective. For the consumer, nothing really changes. You still have the option to watch ad-free. There’s just an additional option.

For the streaming service, there are many advantages. First of all, they retain more customers. They have a higher degree of price discrimination. Meaning, they can further exploit the individual's willingness to pay and retain more customers.

They can also charge more money for advertisements than old-school TV because they have a lot more data and thus know the customers a lot better.

In television, they had little knowledge apart of what gender or age group prefers what show or time to watch TV. But not a lot more. They just competed for watch time, and the more viewers they had, the more they charged for advertisement. They came over numbers.

Netflix and other streaming services know a lot more about us. They can target ads better and, therefore, charge a lot more money for advertisements.

Key Players

The three biggest players in the global video streaming market are Netflix, Disney+, and (Amazon) Prime Video. Followed by the two Chinese video streaming providers, Tencent Video, which is part of Tencent, and iQIYi, which belongs to the Chinese search engine Baidu.

Max, the merger of HBO Max and Discovery+, now sits at 95.1 million subscribers, and Paramount+ reported about 63 million subscribers. Apple TV+ remains a black box since Apple still doesn’t release the numbers for their streaming service, but they are quite far behind anyway, with an estimated 25 million paid users (45-50 million combined if you count users that have access via promotion).

The last place on the Top 10 list goes to the Indian streaming service Eros Now. Eros Now works a little differently. They have a premium paid subscription model that works similarly to the paid subscriptions of the big US services and a base paid subscription model that includes single downloads or subscriptions lasting a day or a week.

This article, however, will focus on the North American streaming services since they dominate the biggest markets outside of China.

Netflix

Netflix is the pinnacle of streaming services. It’s the number one judged by subscriptions, it has the most global users/viewership, and the most noticeable brand. On the map below, you can see what video streaming services are preferred in what region of the world.

Netflix clearly dominates the Western world, being number one in Europe, North America, and South America. While North America looks to be dominated by Prime Video, this is only because, as we’ll discuss in more detail when we talk about Prime Video, Amazon doesn’t differentiate between Prime and Prime Video members.

If we adjust for that fact and only count the users of the streaming services, North America is also covered in red with a white Netflix logo.

Netflix entered the market and revolutionized the entire entertainment and video industry when it turned from an online “DVD‑by‑mail movie rental service” into a video-on-demand service in 2007.

Since then, it has kept its first-mover advantage and become the most subscribed to and watched streaming platform. You know your brand is strong if your brand name becomes the synonym for an activity. If you want to research something, you “google” it. If you want to calm down and relax, you “Netflix and chill.”

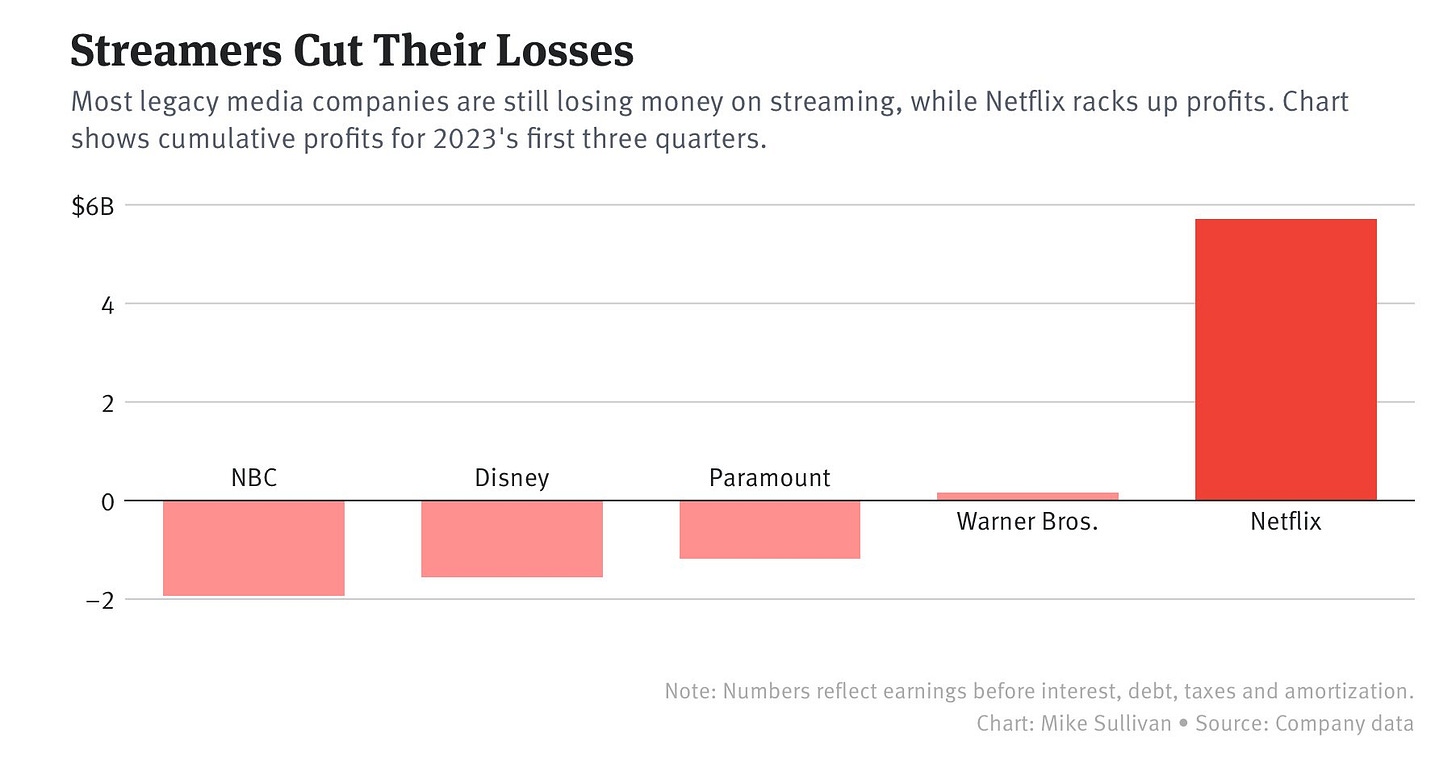

Real brand strength is showing up in the numbers, and Netflix’s numbers are proof of that. Netflix’s revenues have gone up almost ninefold since 2012. But more importantly, they’ve finally started to turn the business model profitable. Something that most competitors still struggle with.

To understand Netflix better and later draw comparisons with the competition, let’s take a look at the most important metrics for a streaming service. What are the financials broken down to the level of a single subscriber?

The first important metric is the Average Revenue per Membership. That is, how much does the average subscriber pay? In this case, I’ve broken down the revenue to the geographics of the subscribers. The numbers are from the quarters of 2021 to 2023. Throughout this article, we will compare these numbers to the competition whenever possible (some do not disclose these numbers).

The second metric is Net Additions or Losses of Paid Memberships. As you can see, there have been losses in the first two quarters of 2022. This led to a severe sell-off, as we will discuss later. However, one should keep in mind that those losses only amounted to about 2.5% of all paid memberships and thus had little impact on Netflix's overall financials.

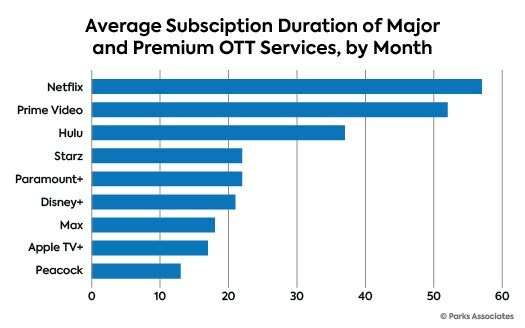

Another statistic differentiating Netflix from most competitors is the Retention Rate of Subscribers. (Paying) Netflix subscribers are the most loyal, with an average subscription time of 58 months. This might be the statistic that shows Netflix's competitive advantage the best. Why Netflix succeeds at retaining subscribers longer than competitors will be discussed later.

We’ll discuss and compare these and other key statistics in the following introductions of the other competitors. Since Netflix is the market leader, I’ll use it as a benchmark for the other key players. In those comparisons, the statistics will give you more context and a better perspective on both Netflix and the company in question than when I list all of them here without comparison or context.

I’ll come back with a conclusion on Netflix at the end when you better understand the industry dynamics and players.

Let’s start with the first competitor.

Disney+

Disney+ is an interesting case in this sector and the one closest to Netflix’s business model out of the four key players. In 2019, when I first heard that Disney would launch its own streaming service, I thought this was an obvious and great idea. Investors thought so, too, and the stock price rallied in the months ahead.

Disney stock gained 130% from the lows of the Covid crash to its peak and last all-time high. Despite having to close Disney parks worldwide and the lack of box office revenues, it was one of the big winners of the recovery. Investors believed in Disney+ and imagined a similar success to Netflix.

Disney ticks all the boxes - they own many of the most valuable movie franchises in the world, and they’re among the most valuable brands in the world. The library of Disney content is unmatched by any competitor.

And the initial subscriber growth of Disney+ made it seem that the hypothesis was right and the service was a big success. Disney reached 100 million subscribers after only 16 months. It took Netflix 10 years to reach that milestone.

Disney itself only planned to have 60-90 million subscribers until 2024. After the massive success, they revisited their goals about a year later and aimed for 300 to 350 million subscribers by 2024.

We are in 2024 now, to be fair, still at the beginning, but Disney’s subscriber count has decreased over the last year and currently stagnates at a little less than half the proclaimed goal. This miss on expectations is another indication that the firms entering the streaming business did not have a realistic idea of how big the market actually is. A beautiful example of why investing based on total addressable markets (TAM) is not a valid investment thesis.

And what’s worse than the stagnation of subscriber growth, is the decline of Disney’s financials in connection with Disney+. After the launch in 2019, Disney’s operating margin tumbled, and cash flows dropped significantly.

And while a short-term setback due to investments in Disney+ was expected, it seems that Disney has made the fatal mistake of turning valuable, high-margin customers (the ones that go to the cinema and spend money on movies and merch) into low-margin customers (watching from home at Disney+) instead of gaining a new kind of customer that they didn’t serve before (more on that in the Customer Perspective Section).

This theory gets further support if we look at the difference between Netflix and Disney+ subscriber growth in recent years. After the fast growth of the first 16 months, in which mostly long-term Disney fans subscribed to the service, the gap between Disney+ and Netflix barely narrowed. In recent quarters, it has even grown wider.

As we’ve discussed above, Disney noticed that subscriber growth will not go on forever and that they have to work on turning the Disney+ subscribers into high-margin customers again.

Like Netflix, they raised prices multiple times and eventually started an ad-supported subscription model. At the beginning of 2022, Disney+ cost $7,99 per month. In December 2022, they raised prices to $10,99. In October 2023, prices were raised again, and Disney+ now stands at $13,99 per month, making it almost double the price of 1 1/2 years ago. The ad-free version is sitting at the old price of $7,99, by the way.

Due to these price hikes, Disney+ was able to increase its revenues again after stagnating in Q4 of 2022 and Q1 of 2023. But raising prices alone will not be the way to success.

One of the most important metrics to track is the Average Revenue per Membership. In the case of Disney+, one paid subscriber currently accounts for an average of $6.97 ($16.29 for Netflix) in North America and $5.93 internationally (weighted average for Netflix is $9.59). To give you a reference point, Disney+ subscribers categorized by region are about 40% North American and 60% international.

So, at the moment, a North American Disney+ subscriber is only worth 43% of a North American Netflix subscriber. An international Disney+ subscriber is worth about 62% of an international Netflix subscriber.

While you can see that Disney+ was able to increase the monthly revenue per paid subscriber by 33% over the last three years and thus worked on closing the gap, those increases were largely due to the price hikes of subscriptions and advertisements. And there is only so much leeway to increase prices and advertisements in the future.

Additionally, Disney+ is spending more and more money on production every year. Since 2021, the production cost of Disney+ content almost doubled. And looking at the subscriber numbers, it seems the new content is not pulling in many more customers.

Consumer Perspective and Quality of Content

Let’s look at the consumer perspective and test the hypothesis that Disney turned high-margin customers into low-margin customers.

Since 2014, Disney has published at least one movie grossing over $1 billion every year, except for the pandemic, until this streak broke in 2023. 2019, the year at which end Disney+ was released, was Disney’s most successful in history, releasing seven movies that crossed the billion-dollar mark.

To be fair, The Avengers: Endgame did end a very profitable and highly successful franchise. However, this can’t be the reason why almost all Disney movies fell short of expectations in 2023, and the general feedback and numbers get increasingly worse year after year.

It’s not as if Disney is not trying. They released 19 movies in theaters in 2023. And while other studios also struggled, 2023 was a year in which hits were released. Oppenheimer and Barbie (A Warner Brothers (Max) Production) proved that it’s not the cinema in general failing to pull in customers. Disney seems to struggle with putting out content on Disney+ and in cinemas.

They don’t know what shows or movies have cinema potential and what should be released on Disney+. Apart from that, it’s simply too much content, at least if you stay in the known universes.

In 2021, there were 5(!) MCU related shows on Disney+. In 2022, another three, and another three are planned to be released this year. However, the number of viewers of Marvel Disney+ show premieres in the US clearly shows that this strategy isn’t working. Every new release gets fewer viewers than the predecessor.

Another problem for Disney is that they even build their theater movies around these shows. For many of their last releases, they expected you to have seen these Disney+ shows. Otherwise, there’s a good chance you had no idea what was happening in the movies.

They limit their customer base by doing that. If I don’t even know if I have enough information to understand the movie's plot, I won’t spend money and time to see it in cinemas. At best, I wait for the Disney+ release and watch it then. That way, there is no risk that I realize quickly that I have no clue what’s going on.

This introduces another problem. This might be one of the rare cases in which brand strength has a negative side effect. Everyone knows Disney, and everyone knows that Disney movies will eventually be on Disney+, often sooner than later. While this might sound like a good thing, it’s hurting Disney in this case. Humans are lazy. When I see a movie trailer, and I like it, I want to watch it. Apart from Disney, I never know if that movie will ever turn up on any streaming platform if I miss it in theaters. So I better go watch it.

With Disney, I know for certain I’ll be able to watch it on Disney+ later. As a customer, the risk and reward is better when I intentionally miss it in cinemas and watch it on Disney+.

All these points add up and cause the consequence that Disney+ is not bringing in another branch of consumers but actually turns the old-school, high-margin Disney viewers into low-margin Disney+ customers.

Consumer Perspective Disney+ vs. Netflix

Netflix doesn’t have that problem, and there are two main reasons. One of them can be tackled by Disney. The other one is structural and won’t be addressable.

First, Netflix can create all sorts of content. They’re not bound to specific universes or characters. They’ve built trust with the consumer that Netflix Originals have a decent quality and are worth our time.

So they can release more content without consumer fatigue and have to spend less money because the viewers aren’t used to cinema-type quality, as is the case with Disney and their universes like Marvel, Star Wars, and many others.

Many shows that Netflix produces do not go viral or become hits on the platform. They are good enough to bridge the time between two big hits but nothing more. But this works. Every now and then, they produce a global hit like Wednesday or Squid Game. Those drive subscriptions. The smaller shows retain them.

They create shows with a spawner-type strategy. Instead of huge investments in one or two shows per year, they release many shows at comparatively low budgets. Some will go viral, while others fill the library: low risk, high reward.

Second, Netflix doesn’t have the “burden” of carrying gigantic other businesses with it. Balancing streaming shows and cinema movies is not an easy job for Disney, and it wouldn’t be easy for any other streaming service. Fortunately for Netflix, streaming is their only business, and they can optimize how they run it without any distractions.

Among the top 4 streamers, they are the only company where streaming is their only business.

Conclusion

I think Disney+ needs a changing strategy if they want to use their strengths, which are there, and simultaneously get back on track with their movie releases.

What I’d like to see as a consumer and what would benefit investors is that they draw a clear line between cinematic releases and Disney+ shows. They need less quantity and higher quality on the theater releases and more Disney+ content untied from the universes that are psychologically tied to cinema releases.

Why not create brands/franchises solely produced for Disney+ and others that clearly focus on the cinematic experience and are worth watching in theater? No one would’ve decided to wait for Oppenheimer until it’s on some streaming platform. If the quality is there, people will watch it in theaters.

This would cut their costs on the production of Disney+ shows, which are way too high compared to the competition, and make box office releases more worthwhile again. It also strengthens Disney’s brand, which is suffering under the current strategy.

Amazon Prime Video

The problem with comparing Netflix to some of its competitors is that many of those company’s streaming services are black boxes. Amazon Prime Video is a … prime example of that (sorry).

Prime Video is a streaming service included in Amazon’s Prime subscription model, together with many other features that belong to the Prime ecosystem. Since every subscriber of the Amazon Prime service automatically counts as a member of Prime Video, comparing numbers to Netflix or other competitors gets a little challenging.

The Amazon Prime ecosystem consists of the following services:

Free shipping (+ 1-Day delivery depending on your country)

Amazon Prime Video

Prime Music

Exclusive Deals (Annual Amazon Event with exclusive deals for Prime members only)

Books & Magazines (A rotating catalog of free eBooks, audiobooks, magazines and more)

Despite Amazon not reporting separate numbers for each of its Prime services, Andy Jassy, CEO of Amazon, stated that Prime Video has been among the top two reasons for Prime members, especially in the US, to sign up for Amazon Prime.

He also said that over 100,000,000 people have watched Lord of the Rings. Now, “watched” might be exaggerated considering the 37% that finished the show. But even if a hundred million people only clicked on it at some point on Prime Video, this would mean that many of the over 200,000,000 Prime users use Prime Video more or less actively.

The quote below by Dave Fildes, Amazon’s Director of investor relations, states a similar bullish look on Prime Video (quote from 2021).

Amazon doesn’t need Prime Video to succeed in the same way Netflix and Disney+ have to (focus on the isolated profitability of the streaming service). Prime Video is not what Amazon wants to make the big money on. It is supposed to drive traffic to the Prime subscription.

Amazon Prime subscribers heavily outspend normal Amazon customers. In a 2018 study, Prime members spend an average of $1400 annually on Amazon, while non-members only spend $600.

In a 2021 study, this gap widened even further, with Prime members spending $1,968 per year on Amazon and non-members less than $500.

Considering this, Amazon’s strategy and approach to Prime Video are different from Disney and Netflix. And it seems to work out well. Remembering the retention of customers, we saw that Netflix and Prime Video are leading these statistics far ahead of the competition.

Netflix is leading this statistic because of its superior content and position in the streaming market. Amazon, however, is more reliant on the entire Prime ecosystem. New subscribers join because of Prime Video and stay for the Amazon Prime ecosystem. A case study like Brazil shows how much potential that strategy has.

It’s one thing if Amazon already is the market-leading online retailer everyone knows and then launches a streaming service on the back of that reputation. Launching the streaming service first and following up with Amazon Prime is much more difficult. Making that work shows that the service actually has enough value on its own to be attractive to customers.

Prime Video also differentiates itself by including a marketplace in the streaming service. While you can stream shows as with any other streaming provider, you can also rent and buy films on Amazon that are not available for free on Prime. You can even subscribe to other streaming services through Amazon.

Unfortunately, Amazon does not disclose any numbers on how much revenue they make through this marketplace-like structure of Prime Video, but according to Andy Jassy, it’s an important part of Prime Video’s financials.

As a Prime member myself, I’m not so sure if that’s actually the case…

Consumer Perspective

I’m one of those Prime members who subscribed because of Prime Video. However, I didn’t subscribe for the typical shows but for the Sports rights that Amazon started acquiring over the years.

They started with rights regarding NFL’s Thursday Night Football games in 2017 and continuously progressed into different countries and sports. In Europe, the biggest deal was their right to stream certain Champions League games.

The focus on sports is another point that differentiates Prime Video (and Disney+) to an extent) from competitors like Netflix, Max, or Paramount+. And I think it’s a perfect strategy for Amazon. Sports rights are expensive and, at least in many European markets, hardly profitable.

But Amazon can take that risk because it doesn’t need the highest margins on Prime Video. It wants Prime customers. And sports rights are a very efficient way to attract new customers—especially users with a high retention rate. If you want to watch the NFL or Champions League, chances are you’ll watch every season and thus stay a loyal subscriber. In contrast, if a hit show is over, you unsubscribe from that streaming service much faster.

Now, looking at the consumer side of Prime Video. I think it’s easy to say that Prime Video has one of the worst user experiences of all streaming services. The integrated marketplace, the bad algorithm of recommended shows, and the annoying fact that almost every show you search for is found (in contrast to Netflix) but not included in Prime Video is getting frustrating quickly.

The user interface was updated in 2022, at a point at which it was almost unbearable, but it remains one of the worst.

Having this frustration in the back of my mind, I also find it hard to believe that the option to buy or rent movies or shows really is such an important part of Prime Video’s financials. I don’t know anyone who ever searched for a show, found out it wasn’t included, and then bought or rented it.

The selection of shows that Prime Video offers (included for free) is also far behind competitors like Netflix, Disney+, or Max. “The Lord of the Rings: Rings of Power” was supposed to change that and become one of the greatest hits of the year. At least that’s what you have to expect from the most expensive TV show ever produced, at $58 million per episode and a total budget of $465 million. But the numbers only look good at first glance. While over 100 million people have started to watch the show, only 37% finished it and the reviews weren’t good either.

The show's costs and mixed reviews are reminiscent of Disney+ and their huge expenses and lack of lasting success.

Youtube (Premium)

While this might surprise some of you, YouTube is one of the biggest players in the streaming industry.

This is another one of the exciting aspects of this sector. Not only are the companies structurally different, but they also produce very different content. Yet, they all compete for the same customer and the same resource, time.

That’s something Netflix understood quickly, while old-school TV completely missed out on this big threat altogether. Everyone competes for your time. What exactly their service is is of minor importance. They all offer long-form content online and need you to spend time on their platform.

And the time you spend on Netflix can’t be spent anywhere. You have to choose. They have to compete.

“Sometimes employees at Netflix think, ‘Oh my god, we’re competing with FX, HBO, or Amazon, but think about if you didn’t watch Netflix last night: What did you do? There’s such a broad range of things that you did to relax and unwind, hang out, and connect–and we compete with all of that.” - Steve Hastings (Netflix CEO)

Remember this chart from the beginning?

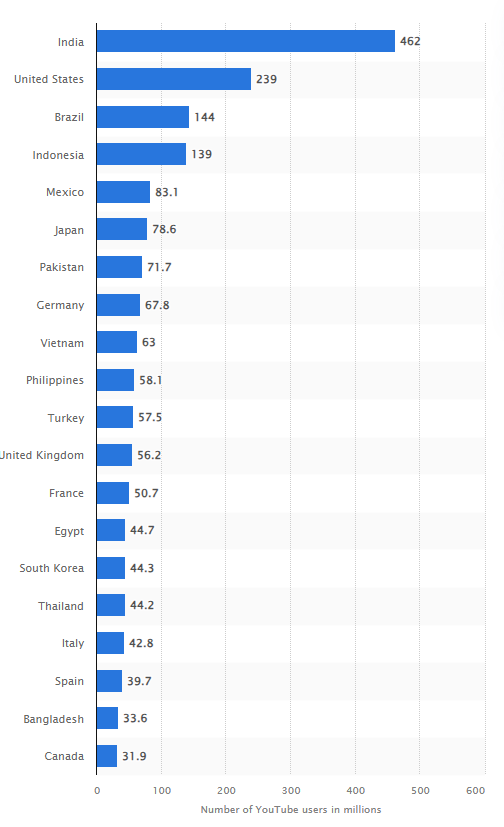

YouTube is not an entrant (new player) but an incumbent (established player) in this market. While many streaming services are primarily active in certain regions, YouTube is global. They have 2.7 billion monthly users and more than 120 million per day.

Every minute, 500 hours of video material are uploaded to YouTube. That amounts to 262,800,000 hours per year. This is YouTube’s advantage compared to all other platforms discussed here. YouTube doesn’t need to create content on its own. The users create content for each other. In that way, it functions much more like a social media company than a streaming service.

As you can see, the lines between streaming services, social media services, and many other services are blurry from a customer and business perspective. You could also include TikTok or Instagram in this debate. However, I chose not to do that for two main reasons.

1. All the platforms discussed today focus mainly on long-form content. That makes a big difference since their business models are based on paid subscriptions and ads. And both of these ways to monetize a platform are a lot more effective on long-form content than short-form content or pictures.

2. If we include every service or company that aims at the customer’s time and attention, there is no end. We would also need to include gaming companies and all other forms of entertainment. As the Netflix CEO once said: “We basically compete with sleep.”

But let’s get back to YouTube and a service that comes closer to what its streaming service competitors offer: YouTube Premium.

Initially launched as “YouTube Red” or “YouTube Music” in the US in 2014, it expanded globally over the years and is counting more than 80 million subscribers (the latest numbers are from November 2022). Considering that the subscriber count was only 50 million a year earlier, it can be assumed that the current number is much higher than 80 million.

The main idea of YouTube Premium is to watch YouTube videos ad-free and be able to download them, let them play in the background, and get access to the wider YouTube ecosystem that includes YouTube Music and YouTube TV.

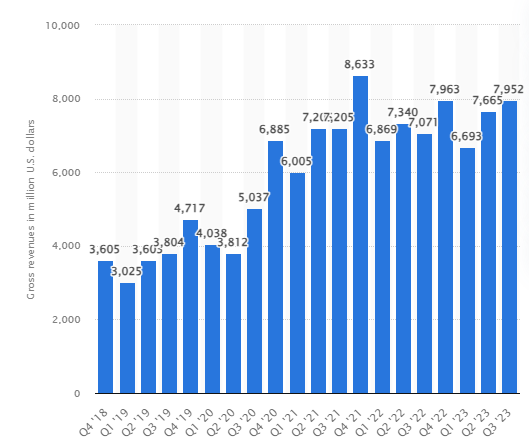

Compared to the previously discussed streaming services, YouTube has been highly profitable for quite a while. In 2022, YouTube generated $29.24 billion in ad revenue.

The revenue of YouTube Premium is reported under “Google Others” and amounted to $29.1 billion in 2022. But Google Others not only includes YouTube Premium, but also Google Play sales and app purchases, and hardware sales.

Because of that, we don’t know how much of the $29.1 billion is generated by the YouTube Premium service individually. We know that of the last reported 80 million paid subscribers, about 27 million came from the US, in which the price is $11,99. That would result in yearly revenues of ~$3.9 billion.

Since the price in the US is among the highest (together with other Western countries), the average of the remaining YouTube Premium subscribers will pay significantly lower prices. The regional distribution of subscribers is not disclosed in more detail, so we can’t calculate how much the remaining 53 million subscribers pay on average.

But judging from YouTube’s user distribution by country and assuming a similar distribution among paid subscribers, it’s realistic that many of those subscribers are in lower-priced countries and that YouTube Premium is a smaller part of the $29.1 billion “Google other” revenues. Assumably, it is in the range of $5-$8 billion.

Another advantage that I see for YouTube is user retention. If you sign up for YouTube Premium, I see little reason to cancel your subscription anytime soon. The main reason to subscribe is to watch YouTube ad-free. That preference doesn’t change every month. Especially not if the long-term trend continues to be so strong towards more, longer, and unskippable ads before and in the video.

Once again, other streaming services have the problem that with every show that ends, users will reevaluate if the subscription is still worth it or if they want to pause it for a while.

Services like Disney+ or Max do struggle with the problem of retention. The bad news for those services is that the only way to increase retention is by putting out consistent, high-quality content. Ecosystem-focused services like Amazon Prime or YouTube Premium have a clear advantage here.

Consumer Perspective

If there is one service among video streaming and social media apps that I wouldn’t want to miss, it is YouTube. YouTube has by far the widest variety of content and the highest addictive potential among streaming services.

However, I must admit that I used an adblocker for many years. Only recently, YouTube has put an end to that. I’m sure there are many new ways to make the adblocker work again. However, as always, humans are lazy.

It doesn’t work anymore, well, then I have to watch ads now. Or I subscribe to YouTube Premium. And after only two weeks of watching ads, I’m almost sure I’ll become a paying subscriber soon. Compared to the last time I used YouTube with ads, years ago, YouTube ads have increased dramatically.

Of all the streaming services, YouTube is certainly the one with the most ads. That makes sense since it is the only one you can watch for free. And while that might be a negative from the consumer standpoint, it’s a positive for YouTube. They have included that many ads, and it does nothing to the usage of the service. If anything, more people sign up for YouTube Premium.

This shows that while YouTube competes for your time with the other services, it still has monopoly-like market power.

It doesn’t play the content game like Netflix, Disney+, Prime Video, Max, or Paramount+. It has proven to work with an amount of ads, that I think no other service could survive with. It is attractive for every customer. No matter how niche the customer's interests are. (Streaming services, on the other hand, have to produce for the masses/mainstream). And they can make a paid subscription (ecosystem-like service) service work.

It seems like YouTube cherrypicks the best aspects from the industries it competes with and bundles them together.

Max

The rather generic name Max is the result of the merger of HBO Max and Discovery+ that took place in May 2023. While HBO is known for quality blockbuster production, Discovery+ will add mostly unscripted and “lower-quality” shows.

This merger poses opportunities and threats. There is the possibility that HBO’s strong brand and reputation for quality content will suffer if Discovery+ adds lower-quality shows to the mix.

The chance of this merger is that Max is now offering content for every consumer out there. The quality shows remain, and the other content is only additional. This concept also gave birth to the name Max. At first sight, it doesn’t look like a smart idea to replace a strong brand name like HBO with a generic name like Max. But the idea was an image change.

The name should communicate to the viewer that Max is the home for all sorts of shows and content, whether sophisticated, funny, casual, or child-friendly.

Whether this will work or fail is yet to be seen. However, I would have considered it a strength for HBO to be known mainly for quality content. The big problem for streaming services, in general, is their similar content. There’s no service that differentiates itself through a specific content genre or quality.

For HBO, this would’ve been the chance to be that streaming service. Yes, Max wouldn’t have the same reach as Netflix, but perhaps they could have attracted customers with a higher willingness to pay. It’s like being the LVMH equivalent of streaming services.

With the addition of Discovery+ content, they play the same game that Netflix, Disney+, and Prime Video play. It’s harder to demand a premium price if you also upload reality shows. Even if the quality content remains and new one is coming, the perception of the service is different. When I see all kinds of reality shows on my screen, I don’t feel that this service deserves a premium price even if the average quality output remains significantly higher than what other services release.

Comparing Numbers and Strategies

Just like the competition, Max lost subscribers in the early quarters of 2023. Starting the year with 97.1 million subscribers, they lost 2 million subscribers, now sitting at 95.1 million—a smaller decrease compared to competitors like Disney+.

Nevertheless, this loss of subscribers and their below-average retention rate (compared to the top 5 streaming services) might have been the reason for diversifying their content.

Max was the prototype for a service that loses subscribers as soon as a blockbuster show ends. Decreasing the reliability on those shows could improve the retention rates. Another option would be to make the annual subscription plan more attractive. However, this might be difficult at this point, considering the competition and, thus, vast alternatives for customers.

Fortunately, Warner Brothers reports specific numbers for their Direct-to-consumer segment (Max), which makes it possible to compare the Average Revenue per Membership of $7.82 to its competition.

If you remember Disney’s and Netflix’s numbers, you’ll realize that Max does outperform Disney ($6.97 for US customers and $5.93 international) but underperforms Netflix ($16.29 for US customers and $9.59 international) by quite a wide margin.

Throughout 2023, Max was able to increase ARPM by ~5%. The increase resulted from subscription price hikes as well as the introduction of ad-light subscription models. This is a significantly lower increase than the 30% of Disney+. Time will tell if Disney+ manages to sustain these growth rates or if it’ll plateau at a level close to Max.

Given that the initial potential of price hikes and ad-free options is exhausted, it will get more challenging to grow ARPM in the future.

As with many other services, Max is barely profitable due to the high costs of producing new shows.

Because of that, CEO David Zaslav has decided to license certain shows to other streaming services. Primarily Netflix. Shows like Band of Brothers, Ballers, Insecure, The Pacific, and Six Feet Under are heading to Netflix in a co-exclusive licensing deal. This seems like the beginning of another major change in the streaming landscape.

Other studios have decided to go a similar way, with Netflix being the service to which most shows are licensed. This new development either turns out to be a big winner for the studios that sell their shows, or it puts an end to the streaming wars, and only the two or three biggest remain while the other services switch their focus to producing shows and selling them.

Right now, I see two advantages to licensing shows to Netflix. The first is obvious. You make quick money to repay debt or fund the production of new shows.

The second would be that Netflix has proven to be the best way to popularize a show. If you want to start a new show that is planned to have more than one season, you could sell the first season to Netflix, hope that it will become a success, and release the subsequent seasons or spin-offs on your own service.

As I said, this would be the optimal scenario. It might also happen that, in the long run, it is more profitable to produce shows and then sell them to Netflix or Prime Video instead of publishing them yourself.

However, while this might be an option for the smaller streaming services that are unlikely to grow into the ranks of the top 5, I don’t think that Max is planning on doing that. A subscriber base of 95 million people should have more earnings potential than licensing out shows to other streaming services.

Investing in Streaming Companies

We’ve discussed the similarities and differences of the big video streaming services. Generally, what stands out is the competitive nature of the sector and the fact that the only companies that are indeed profitable at this point are YouTube, which benefits from the fact that it doesn’t play the typical streaming game, and Netflix, which can leverage the strengths of being the industry leader.

To discuss whether investing in streaming companies makes sense, we need to highlight two points.

1. Are there competitive advantages that a company can use to escape the streaming wars and competitiveness in the long run?

and, as always…

2. What is the price you currently have to pay for these companies?

Until now, we’ve isolated the streaming businesses from their parent companies. But if you want to invest in them, you must buy the whole company. For Netflix, this doesn’t change much. For Prime Video, this means you need to invest in Amazon, a YouTube (Premium) investment is possible through acquiring shares in Alphabet (Google), and Disney+ would result in an investment in Disney.

Let’s start with the simplest alternative:

An Investment in Netflix

Netflix shares currently trade at $485, which results in a market cap of over $220 billion and a P/E of 48x. However, this is far from an all-time high for Netflix. In October 2021, the shares traded above $680. What followed was a 75% drop on reported stagnation of subscriber growth, which we already discussed before.

This caused a significant multiple contraction, and the P/E investors were willing to pay went from 66x to 15x. This situation is a prime example of what can happen to a stock bought at high multiples.

Without a change in the business itself, the earnings and subscriber growth decline was small and temporary, the stock got crushed.

Netflix has a history of being volatile in earnings season, but the price reactions seen after subscriber growth stagnated were more intense than usual and might have initiated Phase 2 of the streaming services in which they realized they had to optimize for profitability instead of just user growth.

As you can see below, the earnings themselves weren’t even disappointing. They beat the estimates and showed significant YoY growth. However, investors were paying for subscriber growth first and foremost.

Since Netflix’s P/E went up significantly again, the question is, what are investors paying for now? Is it subscriber growth once again? Or is the outlook that the business became profitable and can build on that?

Without answering this question, we can’t invest in any of the streaming services. We need to know what investors expect and what they pay the premium P/Es for.

Judging by the shortsightedness of investors, I suspect that subscriber growth is a significant part of the equation again. And as we have worked out in this article, neither the companies nor the market knows what growth to expect in the future. The TAM (total addressable market) and short-term potential were overestimated by a wide margin before, and this is likely to happen again.

In my opinion, Netflix is currently priced for a “keep it up.” Subscriber growth needs to continue as it did in the years prior to the stagnation while, simultaneously, the company becomes more profitable and increases its competitive advantages and industry position.

This might work for some time, but considering the ongoing high level of competitiveness within the sector, I find it hard to believe that we won’t see another disappointing quarter sooner or later.

With that in mind, Netflix is a buying opportunity whenever the P/E comes down to a level I’d consider realistic for a company growing in the low double digits. Perhaps a level of ~20x. As usual, this is me being very cautious with downside risk. But if there is a sector and stock that proved this method right in recent years, it’s Netflix.

Also, while it might take patience, it has only been 1 1/2 years since we saw these levels.

An Investment in Disney

To own Disney+, you have to own Disney. But Disney had a tough couple of years, going from an all-time high of $197 on March 12th, 2021, to less than half of that at $91.

As mentioned when we discussed Disney+ above, the streaming service launch initially drove up the stock price significantly, and Disney was one of the biggest beneficiaries of the Covid recovery. However, since then, Disney+ has shown two very different sides.

One was the fast growth in the first 16 months of the launch. The other was slowing subscriber growth much sooner than expected and a huge pile of costs in connection with producing new content.

Disney+ was supposed to cover the missed revenue of Disney parks and theater movies in 2020 and 2021 and continue to bloom when parks and movie theaters reopen. The second part did not go as expected.

We’ve compared Disney+ subscriber financials to Netflix before; now, let’s compare Disney as a whole to Netflix.

These two charts nicely show the opposing trends of the two companies. While Netflix is in the process of increasing profitability and more and more of its revenues end up in net income, Disney is currently heading the other way.

Netflix is a growth story, and as I said before, you need to know what type of growth investors expect. Disney, on the other hand, is in a turnaround situation. The business is struggling, and the question is whether Disney can escape that trouble and regain its old strength.

This deep dive focused on the streaming sector and thus only on the Disney+ part of the business. I’ve given you my thoughts on that part of the business, why it currently struggles, how it damages Disney overall, and what I think needs to be done so that Disney can minimize the damage and benefit from its strengths again.

In the process of writing this article, I got interested in the Disney situation, and I’ve decided that I want to research the company further. Thus, the February Deep Dive will be an in-depth valuation of Disney.

I think this makes sense. This article wasn’t a valuation but a sector deep dive. But following up with valuations on the companies discussed today makes sense now that we already have so much background knowledge.

The same logic applies to the valuations of YouTube, Amazon, and Max. The streaming services Prime Video and YouTube, and even more so YouTube Premium, are way too small to act as a foundation for investment decisions on Amazon or Alphabet.

Max is a lot closer to Disney and Netflix. Perhaps it would make sense to write the Deep Dive Valuation on Disney and Warner Brothers… let me know what you think. What would you prefer?

Anyway, I’ll come to an end here and while away the evening with an episode on Netflix. Or Disney+. Or maybe Prime Video… YouTube?

Whatever, see you in the next one! (Leave a Like if you enjoyed the read ;)

My Current Portfolio:

My Latest Research:

Here’s my Investing Checklist (Free for all Paid Subscribers):

https://danielmnkeproducts.com/