Howard Marks Investing Memos - 7 Key Learnings from Six Decades of Investing

Howard Marks is one of the greatest investment thinkers and philosophers of all time. For three decades now he writes down his wisdom in so-called Memos.

1. Market Efficiency (and its Limitations)

Efficient Markets:

The general theory about markets is that they are efficient. Thousands of intelligent and highly-trained investors spend a great deal of time gathering information about companies and other assets and interpreting what it means for their value.

Thus, all available and important information should be incorporated in the market prices, making them “correct.” Correct means that investors can buy this asset and achieve a risk-adjusted return that’s fair compared to all other assets.

This would mean there are no inefficiencies or opportunities where assets provide an excess return. In this world, superior investment skill won’t produce any alpha (outperformance).

This theory makes perfect sense. But is it right in practice?

“In theory there is no difference between theory and practice, but in practice there is.” - Yogi Berra

The number one reason why this theory isn’t entirely accurate in practice is its most important underlying assumption: Rational and unemotional Investors.

Humans are emotional by nature. This hasn’t changed in the past, and it won’t in the future.

Due to this condition, the efficient market theory has its flaws in reality.

Inefficient Markets:

Some markets are less efficient than others. Inefficient markets are…

Unknown

Complex

Controversial

Illiquid

Inaccessible

Markets that fulfill (some of) these criteria tend to offer more mispricings. However, inefficient markets aren’t a free pass to outperformance. It simply offers the opportunity. As always, you have winners and losers in these markets. Even in an inefficient market, not everyone can be above average.

2. Understanding Risk

In academia, risk is called volatility and measures the range of fluctuations over a period of time. But for an investor, this definition of risk seems insufficient.

“Volatility can be an indicator of the presence of risk - a symptom - but it is not risk itself.” - Howard Marks

So, what is risk?

Risk is the probability of a permanent loss of capital.

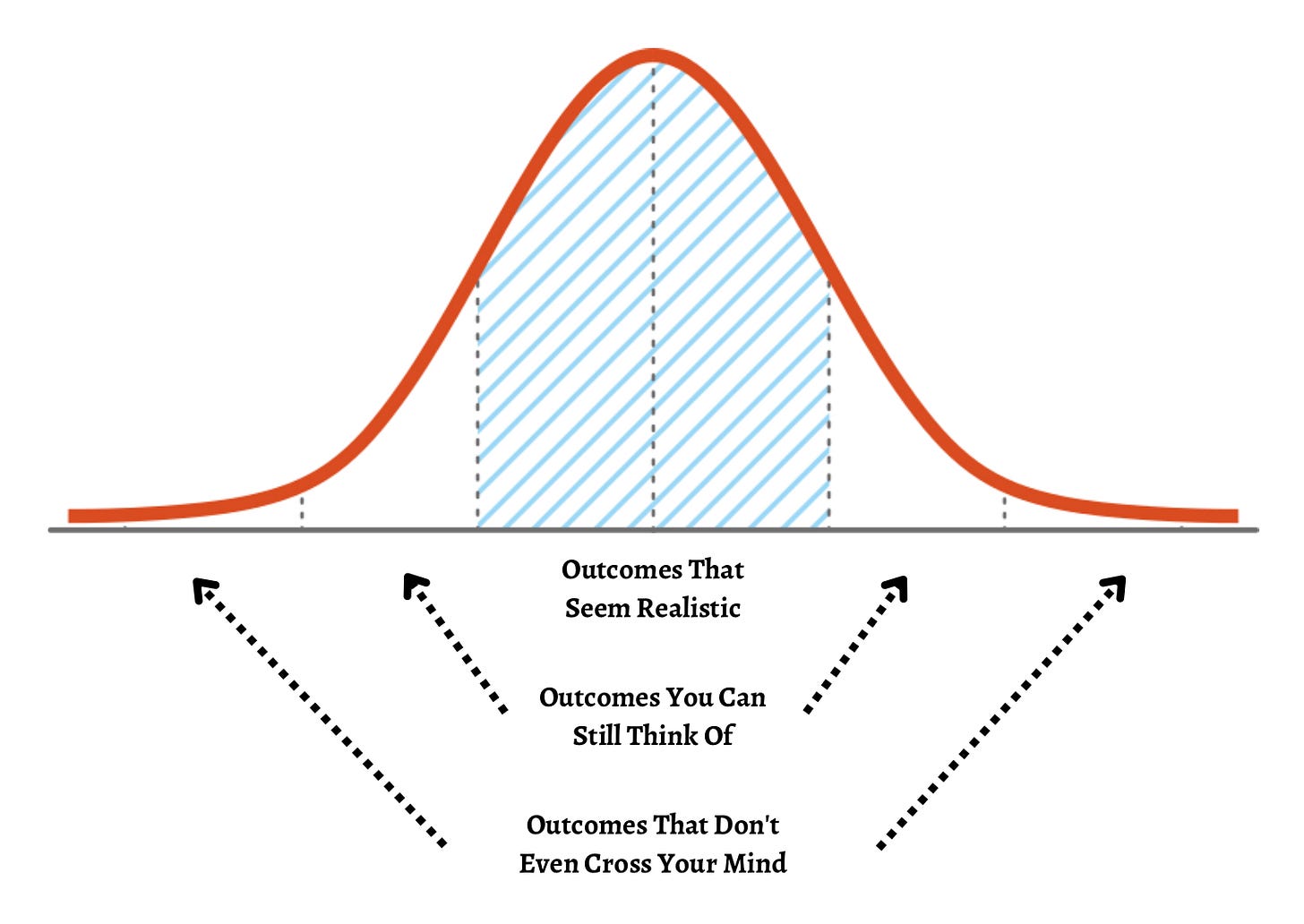

We can think about the future as a probability distribution, and we never know which outcome will happen.

We wouldn’t even know if we knew the exact probabilities and all possible outcomes.

The most unlikely things happen all the time, and the most certain things fail to happen all the time.

‘We live in the sample, not the universe.” - Chris Geczy

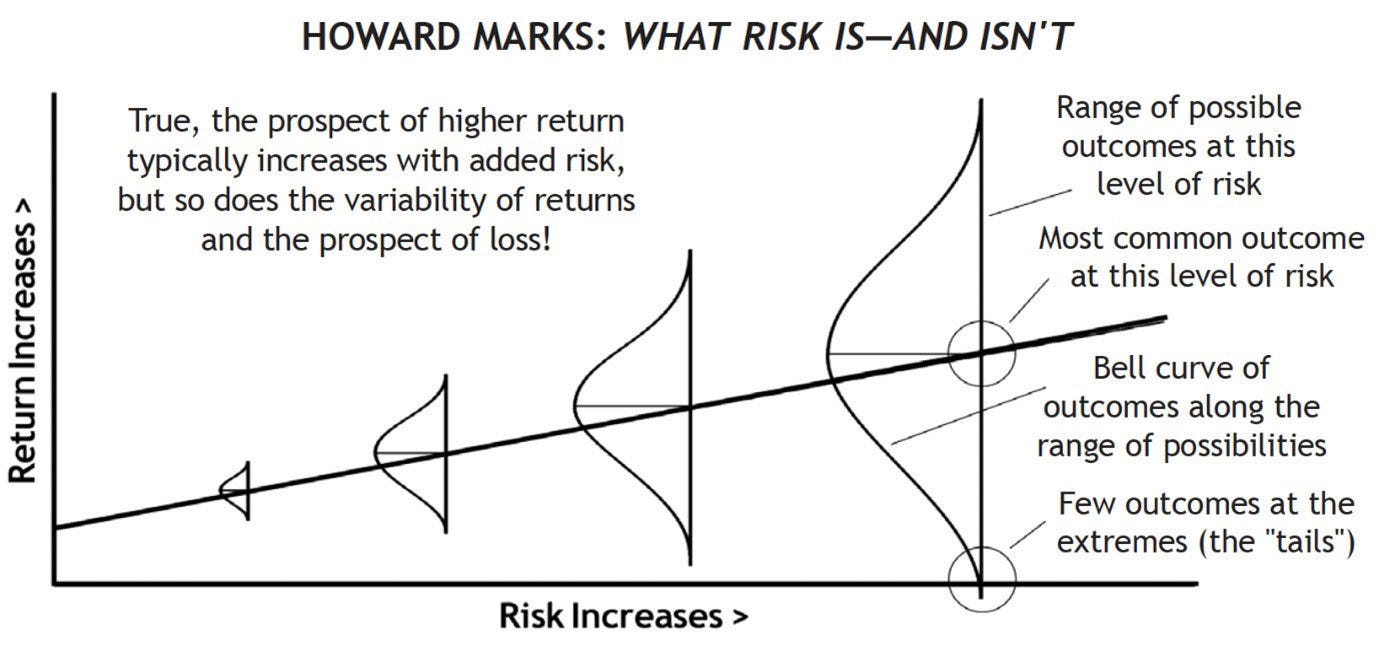

Marks has created an excellent graphic that is far more precise and does a better job of explaining risk than the simple risk-return relationship taught at business school.

The basic assumption that taking on more risk offers more return is still part of his idea (represented by the rising line), but Marks added ranges of possible outcomes to the graph that we’ve seen before in the normal distribution above.

If you want additional content and support my work, consider becoming a Paid Subscriber.

Features for Paid Subscribers are:

Monthly Deep Dives/Valuations of Companies

A Comparative Intrinsic Value Sheet with all analyzed Companies

Free Access to all the Products I’ll release (My Investing Checklist System is already online)

Direct E-Mail Access to Me

A Community Portfolio starting with $1,000

(If you’re a student, message me, and you’ll receive a discount):

3. Second-Level Thinking

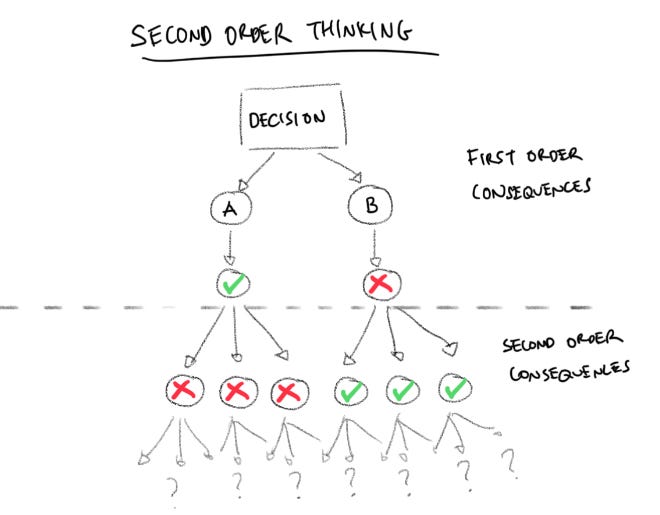

To invest better than others, one must think better than others.

Our go-to thought process is based on First-Level Thinking. We see a problem and look for ways to solve it. We solely focus on immediate consequences and neglect further consequences down the road.

Second-Level Thinking is about first- and second-order consequences. It’s more complex and takes into account questions that come up after an initial action is taken.

First-level thinking is simplistic and superficial, and just about everyone can do it (a bad sign for anything involving an attempt at superiority). All the first-level thinker needs is an opinion about the future, as in, “The outlook for the company is favorable, meaning the stock will go up.”

4. The Route to Outperformance

The biggest question in investing remains the question of how to achieve outperformance. What can you do? What strategy must you use to come out ahead?

The initial reaction of humans is to aim for the next Apple, Microsoft, Google, or even Bitcoin. But looking at statistics and the historic outperformers, another strategy seems far superior.

The strategy of “a little above average.”

While most people seek phenomenal returns that outshine every other investment, a little above average is the secret. The longer your time horizon, the more important this gets.

The problem with swinging for the fences and chasing the next outstanding investment over and over again is the missing margin of safety in those pursuits. The best foundation for above-average returns is the absence of disaster.

As Marks used to say:

“If you avoid the losers, the winners will take care of themselves.” - Howard Marks

5. Microeconomics 101

There are two principal factors that determine whether an investment will be successful.

1. The first is the intrinsic/fair value of the underlying company. The intrinsic value is the price of the business at which it is fairly priced for the quality it offers.

Intrinsic value is not a precise number, although it sounds like it should be. It’s a range. That range depends on many factors, among them are the future cash flows of the company and the rate at which you choose to discount them.

That means you can come up with a different intrinsic value than someone else. Even if you estimate the same future cash flows.

2. The second factor determining investment success is price. Think of the intrinsic value as a, more or less, straight line and the price fluctuating around that intrinsic value line.

When the price is below the intrinsic value line, you can buy the company at a discount. When the price is above that line, you overpay for the company.

This connection between price and intrinsic value also means that a good investment doesn’t require a good company. At the right price, every company can be a good investment.

A bad company could be characterized by a declining fair value line. If the price line is below that fair value line, however, the investment would still offer good returns.

“Everything is triple-A at the right price.” - Howard Marks

6. Macroeconomics 101

Everything moves in cycles. And cycles are the result of emotional decisions by market participants. The pendulum swings between Fear and Greed. While it spends most time in the middle (a healthy mix of optimism and pessimism), sometimes it starts swinging more intensely and approaches one of the extremes.

The interesting thing about this metaphor is its “self-healing” nature. A swing to one extreme is inevitably followed by a move in the opposite direction and eventually a return to the middle.

Investors with a good feeling for market extremes, can profit from the fear of other investors by buying cheap: “Be greedy when others are fearful.” and avoid trouble when the crowds are greedy.

Marks usually doesn’t believe in forecasting macroeconomics. However, there were a handful of times in his six-decade career where he felt comfortable having an opinion on the macro environment. Every time, it was when the pendulum approached one of the extremes.

7. Knowing What You Don’t Know

There are two schools in investing (and basically in life). The “I know school” and the “I don’t know School.”

Most investors belong to the first category. This is how you spot investors of the “I Know School”:

They think knowledge of the future direction of economies, interest rates, markets, and widely followed mainstream stocks is essential for investment success.

They’re confident it can be achieved.

They know they can do it.

They’re aware that lots of other people are trying to do it too, but they figure either (a) everyone can be successful at the same time, or (b) only a few can be, but they’re among them.

They’re comfortable investing based on their opinions regarding the future.

They’re also glad to share their views with others, even though correct forecasts should be of such great value that no one would give them away gratis.

They rarely look back to rigorously assess their record as forecasters.

If there is one word that characterizes this type of investor, it’s confidence. Confidence in their abilities (which is not a bad thing) and confidence in their ability to know what the future holds (this is a bad thing…).

The “I don’t know school” generally doubts their ability to forecast the markets, interest rates, or anything at all. They know the best they can do is take an educated guess. And since that might not be enough, they choose not to participate in the game of forecasts.

Amos Tversky, the colleague of Daniel Kahneman, once said:

“It’s frightening to think that you might not know something, but more frightening to think that, by and large, the world is run by people who have faith that they know exactly what’s going on.” - Amos Tversky

That’s it for today!

If you enjoyed this post, feel free to share it on X so more people get to see it! Thanks, and have a great weekend!